Imperial Despotism Has Never Looked This Good

FIRST IMPRESSIONS: Songs of Syx transfixes the mind and the eye

IMMIGRANT SONG

We had a grand old time last week discussing the greatness of Morrowind’s modern fanbase and angrily proscribing the thought of an official remake — that newsletter did exceptionally well for us, and I’m delighted to see that so many of you are similarly touched by the delirious fantasy of a major publisher actively supporting its fans’ noncommercial projects. In the time since, I’m back to playing video games instead of lamenting the state of their industry, and I’ve got another tantalizing-if-unrealistic fantasy to share with you this week. To wit, that of a government that enthusiastically provides for its people’s happiness and prosperity.

More specifically, I spent about a dozen hours with a little indie gem called Songs of Syx. It’s a colony simulator with much of Dwarf Fortress and RimWorld about it, but it’s got some fascinating characteristics all its own that make it an irresistible subject for analysis. It’s a colossus of artistry even in its technically incomplete state, so I thought I’d tell you about my early impressions and dig into what makes it so special to my eyes.

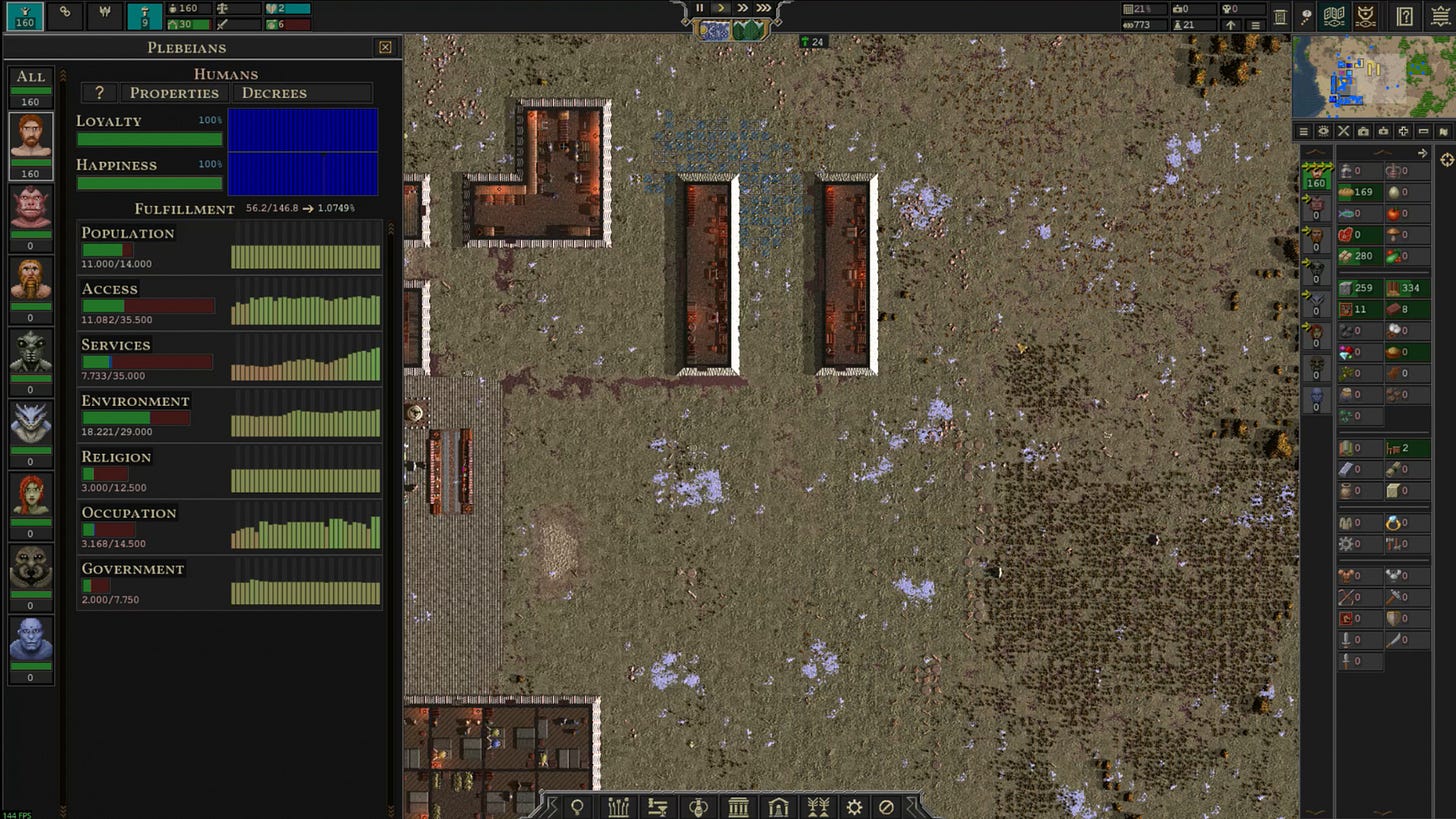

At its core, Songs of Syx is a colony sim. Or, in more accessible terms, it’s a game about occupying a tract of unspoiled land with a small crew of intrepid frontierspeople, bending nature to their will, and gradually expanding into an industrial behemoth capable of political dominance. Like most games of its kind, it’s built atop a staggeringly intricate simulation of people, their economies, and the labors that support both. Rather than directly controlling your plebeians, your job as despot is to designate orders for construction, trade, and management that your people will obediently carry out in between meals, prayers, and lavatory visits. If your decisions are wise and your will ironclad, the simulation rewards you with the spectacular evolution of your humble frontier party into a map-spanning metropolis, whereupon you’re free to spread your peaceful ways by force of arms.

Best of all, SoS is a proud representative of that class of games we so vigorously adulate here at The Spieler: a vision sprung from the mind of exactly one inspired creative, then realized in artwork and code by the very same. It was released into Early Access in September of 2020, where it’s remained despite what looks and feels like a feature-complete build and an astonishing sheen of polish in almost every aspect. I very seldom shell out for games during their pre-release phases, but long-time readers know I’m willing to make exceptions for projects that can back up truly novel ideas with high-quality implementations. Songs of Syx is very much one of those games.

So, here’s the plan for this week: in the first couple of sections, I’ll perform my due diligence and share my impressions of the game as a technically incomplete but nevertheless robust commercial product. Afterwards, I’ll drop the façade of consumer advice and gush for several paragraphs about how thoroughly impressed I am by the aforementioned novel ideas. Do let me know what you think — this is hardly the most accessible game I’ve covered, and I’ll be curious to know whether you find its design and presentation compelling enough to shine through the thick layers of tabular data and bar graphs.

THE GOOD

The first and most remarkable aspect of Songs of Syx, with which I’ll bookend this newsletter, is its standout visual design and the clever ways it’s integrated into primary gameplay. Let’s begin with its superficial appearance. You see, over the fifteen-ish years I’ve been playing colony sims, I’ve come to expect a fairly spartan standard of artwork from the genre. By the mid-2010s, I was so acclimated to the blocky tilesets in Dwarf Fortress that the simple, high-contrast vector art in RimWorld caught me by surprise and felt almost revolutionary. I was similarly impressed by the dimensionless (and unaccountably off-putting) artwork in 2019’s Oxygen Not Included, which was, at the very least, hand-drawn and characterful. Then the Dwarf Fortress guys finally got money together to pay some 2D artists, and the 2022 Steam version’s tiles impressed me anew despite their continued lack of depth or animation. I figured there was a sort of implicit compromise in the design of these projects: in return for a dense, layered, and deeply interactive simulation, you’re to put up with serviceable but uninspiring artwork. After all, the simulation is the core of the experience, and the visual element is only there to convey its signals to your brain by way of the optic nerve.

...or so I thought, until I started seeing gameplay footage of some new-fangled colony sim with dynamic shaders, character animation, shadow-casting, and a gorgeously evocative representation of nature. Had Bierstadt painted in pixels instead of oils, I’m certain he’d have come up with a sun-drenched landscape not unlike a Songs of Syx screenshot. The outward visual appeal is only the beginning of the game’s aesthetic mastery, though — its gameplay integrations deserve a much more thorough analysis, to which I’ll return after we’ve finished the review bit. Before that, there’s a couple more standout features to which I’d like to pay homage.

First, let’s talk pacing. In my experience, the nature of downtime is a pain-point common to almost all colony sims. It comes down to the nature of temporal simulation — in order for a cause to produce its effect, time must pass, and this becomes a major source of boredom and disengagement when the period between instantiating a cause and awaiting its effect passes a certain, limited threshold. For example, suppose I designate a strip-mining operation in Dwarf Fortress or RimWorld. When nothing happens, I realize that my miners are all busy sleeping, drinking, or sleeping off drink. My recourse is to let the simulation run, tick by tick, until at least one of them gets off his ass and begins to effectuate my queued actions so that I can have my precious morsel of sublime dopamine. I could always distract myself by planning out other game states, but that invariably lengthens the queue and compounds the problem at a greater rate than it compounds the reward.

Colony sims from the past decade often include a control for selectively increasing the simulation speed, but even those are limited by the programmatic complexity of their games’ systems — it’s one thing to play RimWorld at three times normal speed, but one third of a long-ass interval is still pretty long. That brings us to one of Songs of Syx’s most impressive innovations: press the “4” key, and the simulation speed is multiplied by twenty-five. Still fiending? Press it again, and caution is thrown to the wind as the multiplier increases to 250. In a matter of seconds, whole farms are tilled and sown; sprawling city blocks are erected from bare earth; entire forests are felled and their timber hauled away. I can’t overstate how satisfying this gets once when you develop a feeling for it — after you’ve built up some comfort with the core systems and start wrangling the speed controls, you can play this game at damn near the speed of thought. It makes SoS dramatically more time-efficient than its genre peers, and it’s an astounding feat of technical optimization.

Below, for example, my settlers build housing for 100 over a full day. It takes less than ten seconds at the maximum simulation speed.

Finally, I want to talk briefly about the setting and lore. The titular world of Syx is a fantasy land populated by a recognizable cast of pointy-eared prima donnas, stature-challenged mountain-dwellers, and squabbling deities who make pawns of the mortal races. And yet, it owes refreshingly little to Tolkien. At game-start, you select from one of six native species to form your imperial core, of which only the Humans are notably familiar. The rest are either twists on the classic formula or altogether unique: the elf analogues are bloodthirsty cannibals; the not-dwarves don’t reproduce, but spring into existence on a mountaintop; a boar-faced race of vegetarian pacifists serves as the tutorial species; a clade of isolationist reptiles are suitable for experienced players; and an austere, exoskeleton-clad race of humanoid bugs round them all out. Each of these has its own set of preferences and revulsions toward particular civics, labors, foods, and aesthetics. Additionally, some species simply don’t get along with one another on account of ancient grudges, which will cause trouble for the careless despot who compels them to live and work together. The setting’s subversions of familiar tropes and the interactions between them are consistently entertaining and often surprising.

There are also several features of SoS that stick out as entirely unique, deserving of more than a passing mention. But before we get to that, let me quickly air out my one major criticism.

THE NOT-SO-GOOD

Good Lord, is this game ever difficult to learn. For as much as I’m inclined to show leniency toward a solo-developed game that’s technically still in Early Access, it’s frankly bizarre how sparsely documented SoS turns out to be given the size and enthusiasm of its playerbase. For one, in-game onboarding is grossly inadequate. You get a pair of tutorial campaigns whose guided portions took me less than an hour in total, and the sum total of that guidance is barely sufficient to get you through the early game for just one of the six core species. Somewhat gallingly, not a moment is spent on crucial progression mechanics like research and military design.

Now, don’t get me wrong — this is by no means a dealbreaker. After all, I’m a veteran of Paradox’s grand strategy games, and their in-game tutorials are about as effective a tool as a hammer made of custard. Thing is, those games make up for it with massive and all-encompassing documentation on the Internet, most notably through the publisher-supported Wikis. Songs of Syx has an official Wiki of its own, but it’s astonishingly incomprehensive. There’s virtually nothing in the way of strategic guidance or outright tutorialization, and much of the data it lays out simply parrots the in-game interfaces. At time of writing, it’s also several game versions behind the current release. Now, to be absolutely clear, I’m not throwing shade at the Wiki editors, whom I’m sure are trying their best. Fully documenting this immensely complex game is a gargantuan project in and of itself, and there are evidently only six (!!!) people actively editing the Wiki.

Luckily, a significant portion of the community that isn’t editing the Wiki is instead devoting its freetime to making videos and writing Steam guides. The information one needs to get into the game is absolutely out there, it’s just not as forthcoming as your garden-variety Paradox nerd would hope. And so, that’s basically it for criticism. I could quibble about how the writing could use a good pass of copy-editing, but there’s really not much wrong with the game itself. Its major issues are almost strictly of a pedagogical nature, and they’re all the sort that could easily be remediated in time for the forthcoming 1.0 release. I have every reason to anticipate that remediation, or at least a substantial improvement. Besides, it’s not like the sparsity of onboarding and documentation presented too significant a barrier to my enjoyment.

But you know, that sentiment is worth consideration. I only have so much free time, and I so rarely have the patience to figure out complex systems like this on my own. The fact that Songs of Syx overcomes that trend is intriguing, and I think it comes down to how uncommonly captivating I find its design. Let’s conclude for this week by going over this game’s most laudable innovations.

THE UTTERLY UNIQUE

So, now that we’ve laid out the necessary context, it’s time for me to report without a moment’s hesitation that this is both the most beautiful colony sim and the most beautiful scalp-camera game upon which I’ve ever laid eyes. But more importantly — and almost uniquely among games I’ve played in any genre — the visual artistry isn’t just superficial. Aesthetics are a core strategic consideration inseparable from the gameplay itself. I’ll give you just a handful of illustrative examples.

It starts at the most fundamental aspects of the genre’s interface. Where most games of this type have you designate structures and orders in straight lines or rectangular areas, SoS gives you a suite of resizable brushes to literally paint your will onto the game world (there’s an illustrative clip of this just below). It’s remarkable how big a difference this makes — roads, farm plots, and foundations can easily take on naturalistic contours that conform to the landscape rather than the grid, making for cities and transit networks that look as if created by sapient agents rather than the emotionless subroutines that execute your orders. Also contributing to the illusion are the people themselves. Each of the game’s species has its own distinct aesthetic preferences whose satisfaction greatly informs their loyalty and contentment. Some expect roads paved in stone, and some want to live in buildings with rounded profiles. Some want to spend their leisure time surrounded by trees, and others desire plazas and mosaics. If you cultivate a multiracial society, you’ll almost invariably end up with interwoven districts that each have a distinct aesthetic, because the game mechanics themselves directly incentivize you to cultivate beauty in addition to function.

I’m very much outspoken in my belief that games are art, but it’s not often that I can celebrate a game as a great work of visual art in its own right. When the sun begins to set over a growing city among lush forests and crystalline rivers, the effect is jaw-dropping. The pure beauty built into the ground-level design reminds me fondly of Jonathan Blow’s The Witness, surely one of the more visually arresting games I can remember playing. But unlike The Witness, I find Songs of Syx a lot of fun to play.1 The successful merger of those qualities, particularly given that this is a solo-developed project, is a towering achievement of game design.

Finally and relatedly, I want to mention the uncommon authenticity of Songs of Syx in its capacity as a solo-developed game. Over the year I’ve been writing The Spieler, I’ve pretty much never shut up about how intensely I value the authenticity and purity of vision that tend to characterize these sorts of projects, but I must say that SoS pushes it to an almost farcical degree. Just load up one of the developer’s video diaries, watch the first fifteen seconds, and drink in the soothing aura of the garbage-tier recording quality. This is a project inspired first and foremost by artistic passion, a quality of unspeakable value in today’s industry. In an era where the fickle gyrations of the market pressure independent game developers toward soul-crushing and ill-fated efforts at wishlist optimization, I can’t overstate how refreshing it is to see a highly successful solo project like SoS drive hundreds of thousands of sales off the back of dedication to a creative vision.

After all is said and done, whether or not I recommend Songs of Syx is largely conditional on your comfort with the genre. If you’ve already got a colony sim or two under your belt, then it’s an easy recommendation. If you’re a genre neophyte but found any of the above particularly compelling, it’s definitely worth your support and I suspect you’ll find it motivating enough to stick out the intellectually laborious learning process. If you’re both new to the genre and on the fence about this game, I’d suggest checking out RimWorld to see whether or not the simulation-focused gameplay grabs you.

And, naturally, I’d love to hear from you in the comments if you have thoughts of your own about this game, or about the evolution of the colony sim genre more generally. Got a favorite that does something similar? Hate the entire genre and want to vent about it? Tell me about it downstairs, and I’ll see ya next week <3

No offense to Jonathan Blow. Looking forward to Order of the Sinking Star.