INTRO: IGNORANCE WAS BLISS

Say, do any of you remember when we used to log into Windows and be greeted with a photograph of bucolic green hillocks in Napa County? You know, the landscape so tranquil and pure that the photographer just threw up his hands and named it Bliss? I’m reliably informed1 Microsoft liked it so much that they paid bro over six figures for the rights. All you get these days in Windows 11 is that pleated mass of felt. What emotions or fervor is Microsoft’s loose drapery meant to evoke in me? The studio responsible for the wallpaper describes it as a “bold and abstract image that celebrates the redesigned centered menu.”2 There you have it, folks — the state of the art.

As a kid, I spent so many thousands of hours staring at computer screens that the Bliss wallpaper would’ve burned into my retinas were I not left severely myopic from all the exposure to blue light. I used Microsoft Windows almost every single day from about 1997 until late 2023 — I’ve used a toothbrush for less time than that. Even as a lad, I was conscious of the fact that computing technology was advancing at light-speed and that I was growing up in the midst of it. The sonorous, reassuring melody of the startup jingle was like a fuzzy security blanket, and I loved it dearly.

Of course, I began to fall out of love around the same time as most other nerds. That’d be in 2012 when Microsoft succeeded one of the best general-purpose operating systems of all time (Windows 7) with an inferior, trend-chasing act of digital sodomy designed to tickle the pickles of incognizant proto-influencers who wanted their PCs to be more like their flashy new smartphones (Windows 8). There was hope for escaping this morass of nonsense when Windows 10 came out and brought back some of what we liked about Win7, but Microsoft swiftly pissed away all of my goodwill. We’re going to talk this week about the three biggest insights I had from the aforesaid piss, but I should first explain precisely what happened.

I remember The Last Straw™ with exceptional clarity. It was October of 2023 and I was in Chicago for a friend’s wedding, alone in a hotel room. My wife was in the bridal party and preparing elsewhere, so I had several hours to kill and wanted to prototype an idea I came up with on the flight over. I withdrew my fancy MSI laptop and powered it on. By this time, I was used to waiting two or three minutes for Windows to have a glass of scotch and fill its catheter bag in between power-on and login. This time, however, it needed to download a mandatory update and I was on crappy hotel WiFi. So when I finally logged in over forty minutes later, I was seeing red. Thanks to years of therapy, I was able to maintain my composure… until I pressed Start and saw an advertisement for motherfucking Candy Crush on the operating system that I paid over a hundred dollars to license for my personal use.

If any of you were staying at the historic Chicago Athletic Association hotel3 that weekend, then I apologize if you were disturbed by the sound of a man shouting hateful invective about Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer. I couldn’t remember Satya Nadella’s name in the heat of the moment, or else he’d have caught the smoke as well.

As soon as I returned home to my desktop PC, I walked myself through the Arch Linux4 installation tutorial and kicked Windows in the head for good. I can now proudly report that, in the year-and-a-half since, I have joined the small club of gargantuan dorks able to completely abandon Windows without also throwing my life into chaos. This week, I thought it’d be jolly instructive to walk through some of the significant lessons I learned about technology and society from so doing. The Big Three insights I mentioned earlier are that average computer literacy is too low, that proprietary software is becoming ever less necessary, and that the Linux-based PC is the heir-apparent of video gaming.

But before we get stuck in, I should make a professional stand: Linux still isn’t ready to comprehensively replace Windows, and some narrow subsets of the Linux community can be really goddamn aggravating in their obstinate refusal to accommodate people with sub-Turing levels of computer proficiency. If you rely on Windows or other proprietary software for your work or lifestyle, don’t let any fanboy come around and get judgemental — you have my enthusiastic blessing to tell him to fuck off. Or just sternly glare at him, since us Linux nerds tend to do poorly with sustained eye contact.

In an effort to maintain a coherent and realistic perspective, I’ve tried to stay self-aware of the educational priviliges and plain-old luck that inform my opinions below. Nevertheless, the argument to which I’ll return again and again is that we all bear responsibility for our own technological independence, and I’m hoping to prove that it’s not a very difficult hill to climb. Hope you enjoy, and please do feel free to comment or reach out about your own experiences. Alright, without further ado:

AVERAGE COMPUTER LITERACY IS TOO LOW IN 2025

Before college, I think I was taught a grand total of three things in public school technology classes: how to touch-type; how to use office software; and how to use a search engine. I suspect public curricula haven’t advanced all that much since I was being taught on the colorful iMacs of yore — if anything, I worry that the modern schoolchild is less able to accomplish anything productive on a computer in this era of doomscrolling and LLM hallucinations. I used to think it was strange that we learned to use office software and type, but never to code or to operate the computer for non-school-related reasons. For the longest time, I supposed that computers were simply too complex and their workings too nuanced for that kind of study to be worthwhile in an everyday context.

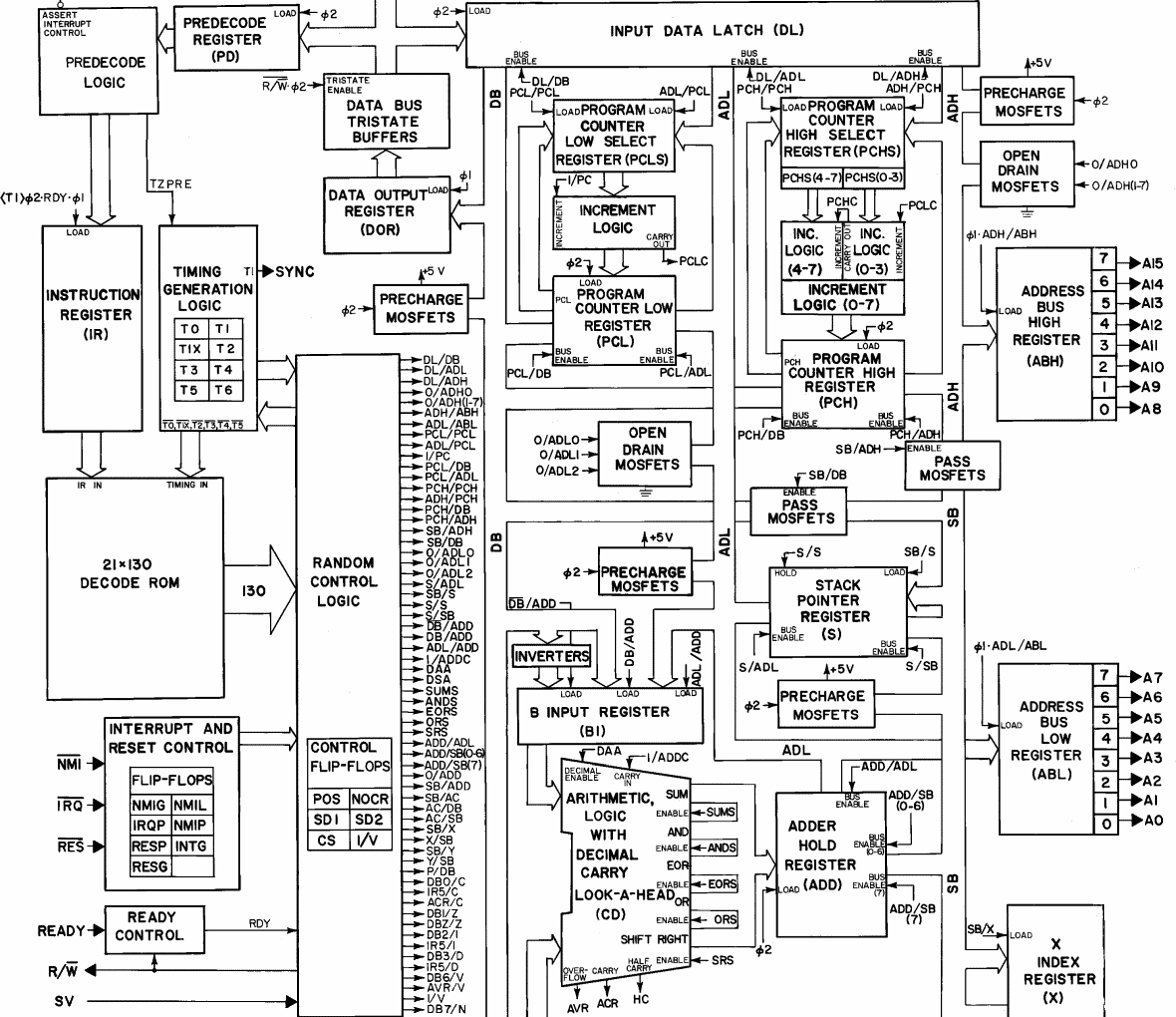

But “worthwhile in an everyday context” is worth dwelling upon. When I actually took a course on computer architecture, I began to appreciate just how little knowledge I had of how computers actually worked at a physical level. The first week of class was eye-opening — we learned the basics of electrical engineering and the physics of how electrical signals are converted into computationally useful routines. That gave me enough of a foundation to intuit how wireless signals, financial transactions, and communication protocols work at a reified, physical level.

In other words, I set myself up to understand the foundational pillars of modern global society, and I realized I could’ve done so myself with nothing more than Google if I had only thought to try. I got to wondering what the world would look like if everybody learned the basics of logic circuits in high school alongside the existing STEM curricula. My hypothesis is that it would significantly alter how the average person understands the world around them in a good way, because it would reduce the discomforting strangeness inherent to relying on forces one doesn’t understand. Just imagine how creepy your own bodily functions would be if you had no knowledge of human anatomy, and I think you’ll get my point. We employ doctors to take care of the really complicated stuff, but easily handle mundane aches and pains ourselves. Why can’t the same be true of everyday computing?

Now, granted: nobody needs to understand x86 processor architecture in order to operate Photoshop or Excel with the best of them, and I’m not saying that everyone should take expensive technical courses on this stuff. But for me, the cognitive disconnect lies deeper than the utility to labor: the vast majority of us, at least in the developed world, are utterly dependent on computer systems to fulfill our basic needs. The purification and distribution of our potable water; the construction and climate-controlling of our dwellings; the moderation of our byzantine transportation-logistics networks; these are just a few examples that came swiftly to mind, and they’re all mediated by remote transactions of resources and information.

It therefore seems reasonable that we should equip folks with a baseline technical knowledge of these systems. We already (try to) teach the natural sciences to hormonal middle-schoolers, presumably out of some succoring notion that doing so will strengthen Western civilization in the long-run. Meanwhile, the PRC’s tech sector is shellacking twelve-figure American AI initiatives with consumer-grade hardware, and I bet it has something to do with their government’s colossal investments into programming education as early as fucking pre-school with simple drag-and-drop engines like Scratch.5

Not every grade-schooler needs to know their way around a transistor, and we don’t need to teach programming in preschool just because China’s doing it. But we’ve got to find some rational middle-ground, because we simply can’t expect a liberated future if we forfeit our agency over technology to techno-aspies like Elon Musk or myself. We’ll soon reach a point — if indeed we haven’t already — at which the average person’s overall capacity for self-determination is limited not by hard work or discipline but by their technical knowledge of the information systems on which they rely. I’ve written before about my frustration with the epidemic of learned helplessness in the face of technological advancement, and this is another prominent example.

At the end of the day, somebody’s gotta know how all this shit works, and I for one am not counting on that somebody’s assumed good faith to protect my interests. With critical information systems, you have to trust that everything is predictably and reliably functional. If you can’t verify that with your own knowledge and skills, then you necessarily have to take someone else’s word for it after they’ve applied their own knowledge and skills. That sort of trust relationship has historically poor expected value for the trusting party, and especially so when money or politics become involved.

PROPRIETARY SOFTWARE IS INCREASINGLY UNNECESSARY

I’ll begin this section by reiterating that proprietary software is still effectively unavoidable for many, particularly those in enterprise or the creative industries who require contractually guaranteeable uptime, support, or cutting-edge features as a matter of business. My own switch to Linux as a software developer was, perhaps unsurprisingly, rather frictionless from a technical standpoint. What astonished me was how quickly I acclimated to the new everyday-business software ecosystem. A lot of my tools already had first-class Linux support, and the rest had excellent and free alternatives that interoperated fine with the Windows ecosystem. I was doing freelance Web development work at the time and, as in many industries, just about 100% of the business was conducted through a Web browser.

That I could easily conduct business with Windows- and Mac-users is a good reminder of the software industry’s trend away from platform dependence. The Web itself, for example, is platform-agnostic by both design and necessity — wouldn’t it suck if you needed a Mac at home to visit websites made on other Macs? There’d be rioting in the streets! Software developers and distributors love that they can count on their users to have access to a Web browser, since they can write code to run directly in said browser instead of trying to predict what mutually incompatible platforms their users are likely to prefer. Similar trends are discernible in the wide proliferation of streaming and crossplay, in which userbases on various systems are similarly consolidated under single platforms.

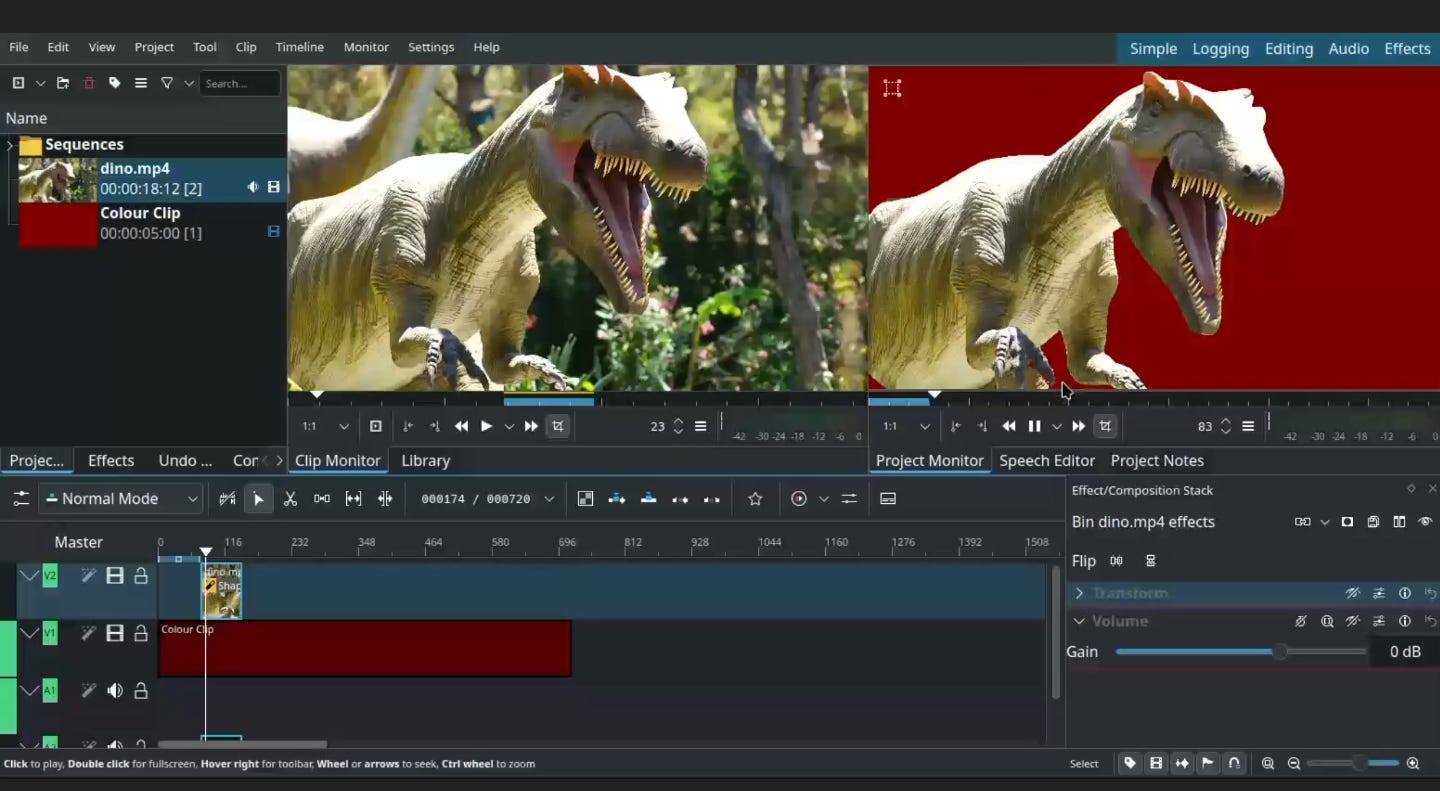

There’s also been remarkable progress in the field of open-source creative software, which now regularly boasts near-total feature parity with expensive proprietary tools, e.g., Photoshop or Premiere. Industry professionals and other creatives at the cutting edges of their disciplines will naturally continue to prefer the proprietary mainstays for as long as those maintain their long-held advantages in enterprise support and feature innovation, which is just fine — with a bit of luck, competition from the open-source community might even incentivize them to de-enshittify their revenue models, though I’m not holding my breath. As for small-time hobbyists like my broke ass, however, professional-grade design and creativity software has never been more accessible.

But my own disillusionment with proprietary software runs much deeper than innovative featuresets, because most of us don’t have highly technical needs of our computers. An overwhelming majority of human labor involving direct computer-usage is still non-technical in nature, representing use-cases like sending email, filling forms, and writing reports or presentations. Budgeting lots of money to license everyday productivity software used to make sense because there were no robust, free alternatives. But in 2025, $100 a year for an Office subscription on top of $100+ for a Windows 11 license is… certainly a choice, especially given that free and open-source office productivity software has been a solved problem for ages now. I’ll concede that a certain percentage of professionals will need this or that proprietary feature in Excel or Access, but then we’re back in the territory of “advanced domain-specific usage.”

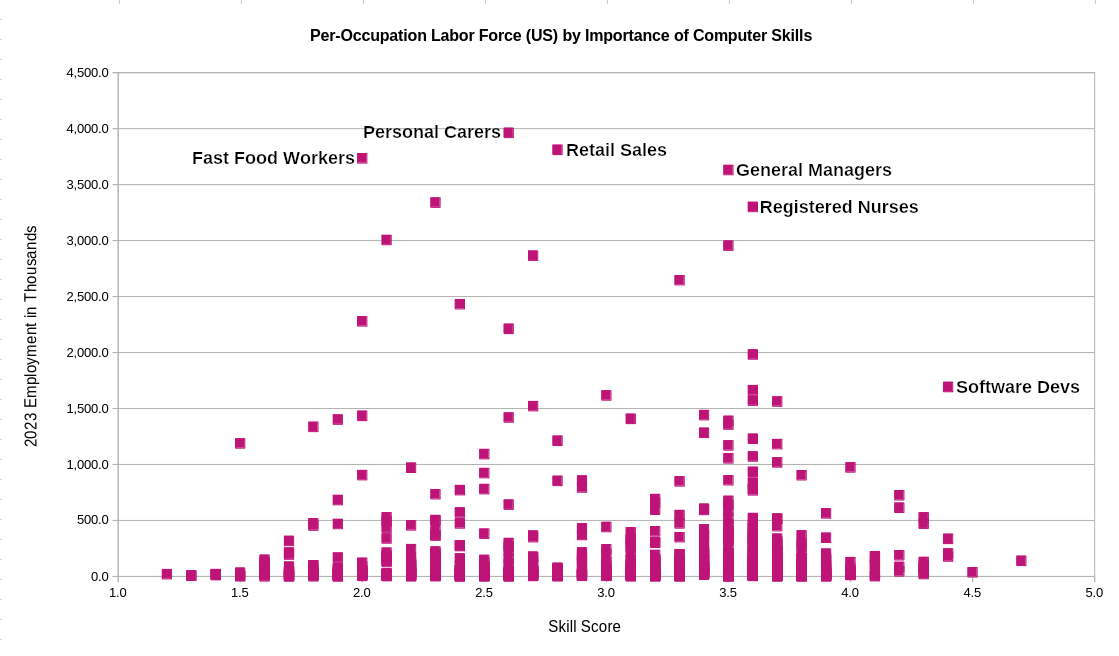

I can even support this with hard data and a nifty graphic, which ought to be good for the newsletter now that Nate Silver has an equity stake in Substack. Have a look at this chart I pulled together using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics in which each point represents an occupational category:6

After some cheeky back-of-the-napkin integration, we see the scope of “advanced technical usage” narrows considerably, and we have to ask ourselves what sorts of work do and do not benefit from the existing model of enterprise software. A registered nurse modifying my electronic medical record? Yeah, I’d like for that to be done with the latest enterprise security updates installed. A manager preparing an expense report for my desk? I think dude will be fine with Ubuntu and LibreOffice. And to tell you the truth, I reckon the manager and the RN could save themselves a packet if all they do on their home computers is check email and browse the Web.

What I hope you take away from this section is that proprietary enterprise software will always have a niche under our existing systems of labor, but the $100 subscription model is not long for the world of everyday computing. My impression from my own work in enterprise IT is this: the average decision-maker still gravitates toward the enshittified status-quo as the path of least resistance, but they recognize that their organizations are being had and are increasingly exploring alternatives. I’ve worked in IT departments at a university and at a large defense contractor, both of which were serially plagued by issues with Microsoft’s enterprise services. At one of those jobs, we had so much friction with license-management that my manager pirated the entire Office suite, put it on a flash-drive, and instructed us to install it in place of the legal version on any computer that came in with Office trouble. It worked like a charm, although I hope no one ever called Microsoft Tech Support for help with any of those cracked copies of Word.

That was a relatively extreme tactic, but I hope it goes to show that the technicians who work the levers of enterprise information technology aren’t all just playing Solitaire and keeping their heads down. Neither are the software developers who, due to altruism or just plain-old spite for aloof managerialism, dedicate their freetime to the engineering and maintenance of free and open-source software towards the benefit of greater humanity.

But that’s enough talk about altruism and advancing the species — I have a few words to say about financial incentives in the big-money gaming industry.

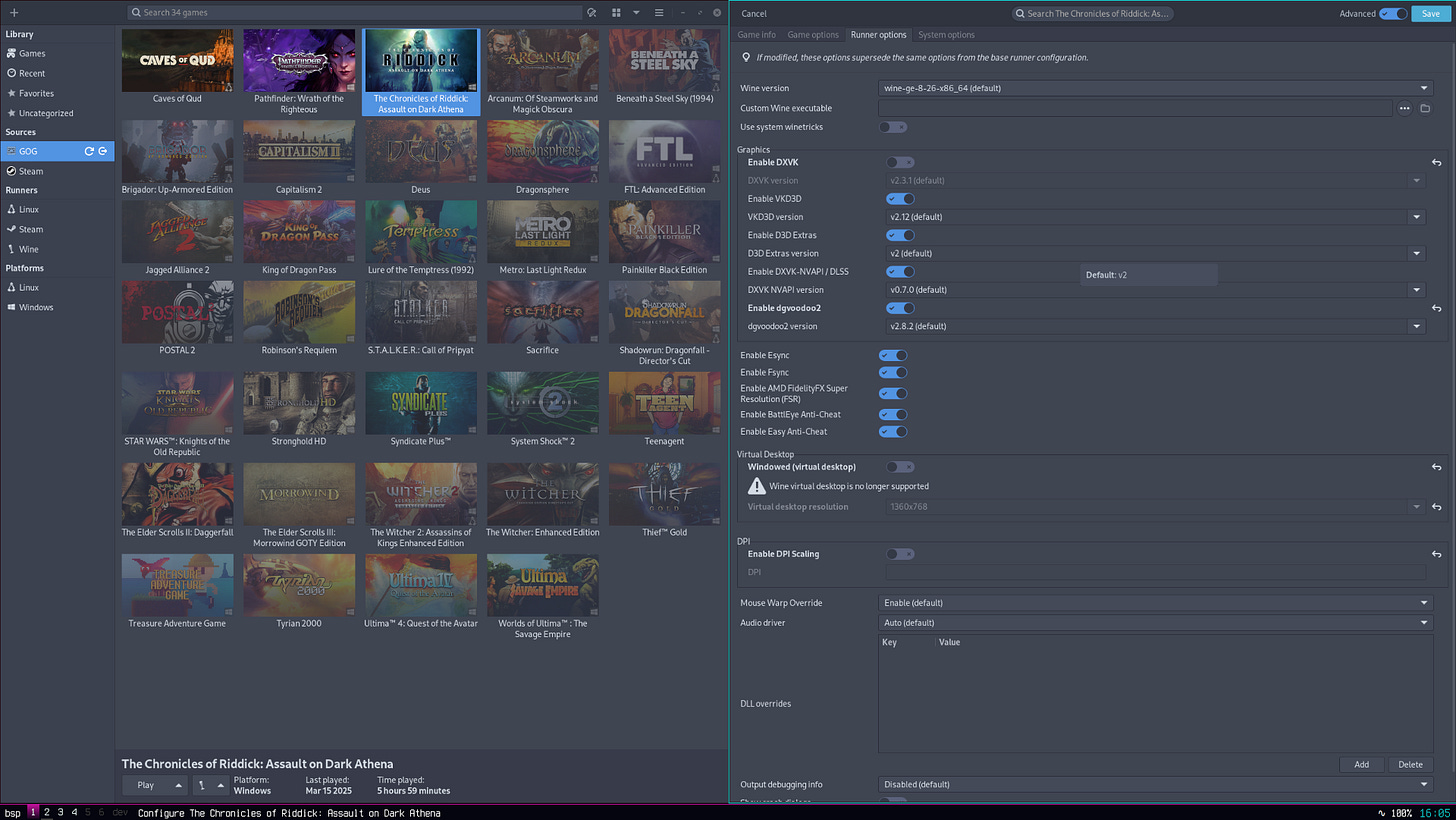

LINUX IS UNDENIABLE IN MODERN VIDEO GAMING

I’ll grant that Linux retains a low market share among desktop PC gamers, but PC gaming has been doing an awful lot of grass-touching lately and is getting away from the desktop. The Steam Deck, Valve Software’s hype-mongering handheld PC, natively runs a version of Linux called SteamOS and has sold over six million units7. That a gamer without advanced technical knowledge can now play several thousand8 Windows games on a handheld Linux machine without any additional friction practically spells it all out.

And even leaving aside advances in compatibility, it has never been easier to distribute a new game or redistribute an old one on every major platform. Fifteen years ago, studios usually had to subcontract another development studio to port a game from one platform to another. Today, a person with no prior programming experience can whip up a game in a free engine and have it automatically export executables for Windows, MacOS, Linux, and even major consoles. So many development teams now find themselves officially supporting Linux even though they predict very small Linux playerbases — it’s just that cheap and easy, so why not?

But I mustn’t downplay the extraordinary push for compatibility and interoperability over the past few years. The fundamental reason why games made for Windows don’t run natively on Linux is simple: when a Windows game sends a command to the operating system, it uses a Windows-based protocol that Linux can’t interpret. But if you can intercept that command and reinterpret it for Linux, then your computer can execute it just fine and the game won’t notice or care. This has been possible for years but is now straight-up intuitive for the liberated gamer, who now has easy access to effective and user-friendly compatibility engines.

WHAT ABOUT WINDOWS-ONLY ANTI-CHEAT?

Before I get too excited, I do want to acknowledge a counterpoint that I don’t think will remain a counterpoint for long: kernel-level anticheat9. If you’re not familiar with kernel-level software, it’s basically anything that runs on your computer at a low-enough level to access whatever it wants without first asking your permission. CrowdStrike is a familiar example with applications to computer security, and you can similarly force your playerbase to install kernel-level monitoring software to make sure they’re not cheating in your online multiplayer game. Kernel-level anticheat is increasingly popular among multiplayer game studios because the teenaged incels who cheat at online games are too feebleminded to subvert it.

I’m going to set aside my many, many qualms with proprietary kernel-level software for now because I understand that lots of gamers are willing to make the trade-off in order to enjoy the games they like, and I have no problem with that in principle. I suppose I also don’t care if Windows sticks around to serve that niche, although I still think those gamers deserve better and more dignified treatment than they’re getting from Microsoft or the major gaming publishers. Instead, I’ll draw your attention to promising alternatives on one hand and the trend of increased Linux adoption on the other.

Where alternatives are concerned, Valve — who pioneer online multiplayer paradigms when they’re not in the hardware market — have been working on AI anticheat for awhile. Counter-Strike 2 is its testbed, and a positive response from that game’s angry-by-default community would effectively spell the end for invasive kernel-level solutions since there would be no need to monitor any data beyond the game environment.10

And even if that doesn’t work out, Microsoft has done such a good job of alienating its consumers that the second-most likely outcome is that enough people adopt Linux for the big studios to start officially supporting it. Money talks, after all. And in the boardrooms of gaming’s top-selling titans, money just won’t shut the hell up lately.

CONCLUSION: VIN DIESEL DID NOT GO TO SPACE JAIL FOR THIS

In our broken age of subscription-based revenue models and enshittified content farming, it’s no wonder that I see folks on Substack nearly every day who’re experiencing their own Last Straws™ and abandoning the Slop-as-a-Service model that we used to think was inevitable. But for as optimistic as this makes me feel, it still brings some discomforting truths into sharper relief — namely, that significant portions of our labor economies and software industries are supported in large part by absurdly inefficient software expenditures from which a handful of megacorporations benefit while the rest of us wait forty minutes to log into our laptops and pay $100 a year to use a fucking word processor.

Things don’t have to be this way, but there are significant structural barriers standing in the way of legislative or regulatory solutions. As usual, I have no intention whatsoever of relying on other people to shore up my liberties on my behalf, so my proposed intervention boils down to “keep taking responsibility for your own freedom.” Many folks are still locked into lopsided relationships with their software providers by professional circumstance, so it’s incumbent upon those of us who aren’t to lead the charge for affordable, user-first computing. Let’s recognize the utility of proprietary and closed-source software where it exists, but work toward a future in which we don’t have to pay through the nose to fulfill our daily responsibilities.

After all, you work hard and pay good money for your posessions — shouldn’t they be serving you?

Til next time friends <3

i.e., I saw this claim on Wikipedia with comprehensive citations, but the original sources were all paywalled.

The accommodations themselves were mediocre, but the service and vibes were unbeatable. Big recommend if you can get a room at a discounted rate.

In case you care: the distro I recommend is “any of them,” but I’d steer you toward Linux Mint if you’re not sure where to start.

This article has a pretty robust overview of the objectively measurable facts: https://equalocean.com/analysis/2020021113558

Peep the raw data here: https://www.bls.gov/emp/skills/computers-and-information-technology.htm

Per Sean Hollister writing for The Verge: https://www.theverge.com/pc-gaming/618709/steam-deck-3-year-anniversary-handheld-gaming-shipments-idc

I struggled to find an exact figure of “Windows-only” games that’re Steam Deck verified, but there are a lot: https://www.protondb.com/explore?selectedFilters=whitelisted&selectedFilters=excludeNative

Tried-and-true anticheat clients like BattlEye and Easy Anti-Cheat are now reliably Linux-compatible.

The idea of AI anticheat in practice is to train an AI model on examples of confirmed cheating so that you can have it compare those embeddings against live gameplay and bust cheaters in real-time. In theory, “confirmed cheating” is borne out by trends in user-input.

Your journey sounds similar to mine in many ways; I’ve landed in Mac, but still use Windows at work. Can you guess which computing environment I find more frustrating?

At this point in time I think that what the major Operating Systems offer are:

Linux*: maximal freedom in exchange for some jank.

Mac: a walled garden, but a fairly nice garden, with enough ability to customize for most uses.

Windows: a walled garden, but one that’s rotten and full of muggers. Only historical monopolies keep it as a mainstay in the workplace and at home.

*I know, I know, there’s lots of Linux distros, and Linux is not an operating system:

https://stallman-copypasta.github.io/

I went straight from the lovely XP to the not-at-all lovely Vista. This was The Last Straw™ that sent my computing to Mac and my gaming to consoles. Have been watching Valve's Linux dabbling the past few years with keen interest.