Post-Nuclear Roleplaying is Good for the Soul

Twenty-eight years later, the classic Fallout games still exemplify the best of the medium

NAVIGATING THE FALLOUT

Tell ‘em, Ron.

In 2077, the storm of world war had come again. In two brief hours, most of the planet was reduced to cinders. And from the ashes of nuclear devastation, a new civilization would struggle to arise. A few were able to reach the relative safety of the large, underground vaults. Your family was part of that group that entered Vault 13. Imprisoned safely behind the large vault door under a mountain of stone, a generation has lived without knowledge of the outside world. Life in the vault is about to change.

Spoken by an unnamed narrator in the silken voice of a then-forty-something Ron Perlman, those words open 1997’s Fallout: A Post-Nuclear Roleplaying Game. It was a unique triumph of RPG design that terraformed the landscape of gaming history almost immediately upon impact. It all but singlehandedly revived interest in roleplaying video games after years of stagnation, and the sterling reception from consumers and critics alike laid the foundation for a worthy sequel barely a year later. Its sagacious writing and the player-driven storytelling it supported were together a salve for a genre long used to thoughtless exercises in context-free violence. It’s remarkable just how little it resembles the properties bearing the Fallout name that followed in 2008 and beyond.

I just finished up a playthrough of Fallout 1 for the first time in about a decade, and I’m happy to report that it still feels like one of the greatest RPGs of all time. Actually, it’s even better than I remembered, probably because of how refreshing it was in contrast to the Skinner boxes and grift-machines that predominate in the commercial industry of today. See, the classic Fallout games1 are often described as highly influential to the games industry that followed, but I reckon that’s only half-true. They had some extremely influential systems — e.g., its choice-and-consequence nonlinearity and the Perk system that probably inspired tabletop roleplaying’s decades-long Feat obsession — but hardly any games ever released are particularly Fallout-like in terms of style and core gameplay.2 One gets the impression that circumstances were perfectly aligned toward their creation thirty years ago, but are now functionally irreplicable.

This week, we’ll talk about what exactly makes that late-nineties Fallout aura so enduringly special. It’s a vision of RPG design as player-driven storytelling engine for which the contemporary market has barely any room, and from which modern game design still has much to learn almost three decades later. Fallouts 1 and 2 present themselves like outlines of stories whose narratives are ultimately filled in by the player through ordinary gameplay. In service of demonstrating that, I’ll sprinkle in some anecdotes from the spoiler-light first half of my most recent playthrough of Fallout 1 as we talk about what makes it so unique. Of course, there’s much more to classic Fallout than just the first game, or even the second — next week, we’ll talk about the independent, noncommercial projects that carry on their legacy better than any game you can find for sale.

CLASSIC FALLOUT AS STORYTELLING ENGINE

If there’s one thing for which I’m earnestly grateful to the Fallout TV show, it’s that its popularity caused the franchise to osmose through the popular culture such that I won’t need to thoroughly explain the setting. So, as a quick recap: there’s no more petroleum! A cartoonishly imperialist America fights a hilariously militarized China. The Reds annex Alaska, so Uncle Sam snatches Canada. Nuclear war in 2077. Some people hide away in underground vaults to emerge generations later, and the rest of the survivors organize into post-apocalyptic proto-nations. Oh, and it’s all passed through an aesthetic filter woven from 1950’s-flavored retrofuturism. Great stuff.

As the game begins, you create a character using Interplay’s in-house SPECIAL3 roleplaying system and tag a few skills in which to specialize. This being my first playthrough in ages, I select the famously safe and versatile combination of Small Guns, Lockpicking, and Speech. Exploration and diplomacy will be much easier, and I’ll become unstoppable with conventional firearms barely an hour into my playthrough. The opening of the game is one of few things that all playthroughs of Fallout 1 have in common: every character is a resident of the enigmatic Vault 13 in southern California, and each story begins with the Vault’s overseer enlisting the player to solve a delicate problem.

“The controller chip for our water purification system has given up the ghost,” explains the overseer in the voice of actor Kenneth Mars. Foreboding news, since the aquifers of California now contain quite a lot of strontium. “I think you’re the only hope we have. You need to go find us another controller chip.” Our sole lead is the known location of Vault 15, about a week’s journey to the east. Vault 13 has at most 150 days’ worth of clean water in storage, so time is of the essence.

That’s quite literally all of the direction you’re given, and it’s part of how the classic Fallout games manifest their extreme open-endedness. Only the bare essentials of the story are shared between playthroughs: you’re dispatched from Vault 13, and the main storyline progresses when you bring a water chip back home. Everything that happens in between those two events is a direct consequence of your decision-making. You can visit whichever of the game’s dozen locations you want and do so in any order. You can retrieve the water chip through peaceful diplomacy, brutish slaughter, or anything in between. But no matter what you do, you’ll develop a reputation among the wasteland’s inhabitants, and the game will react to your decisions to an extent that was practically unheard of before 1997.

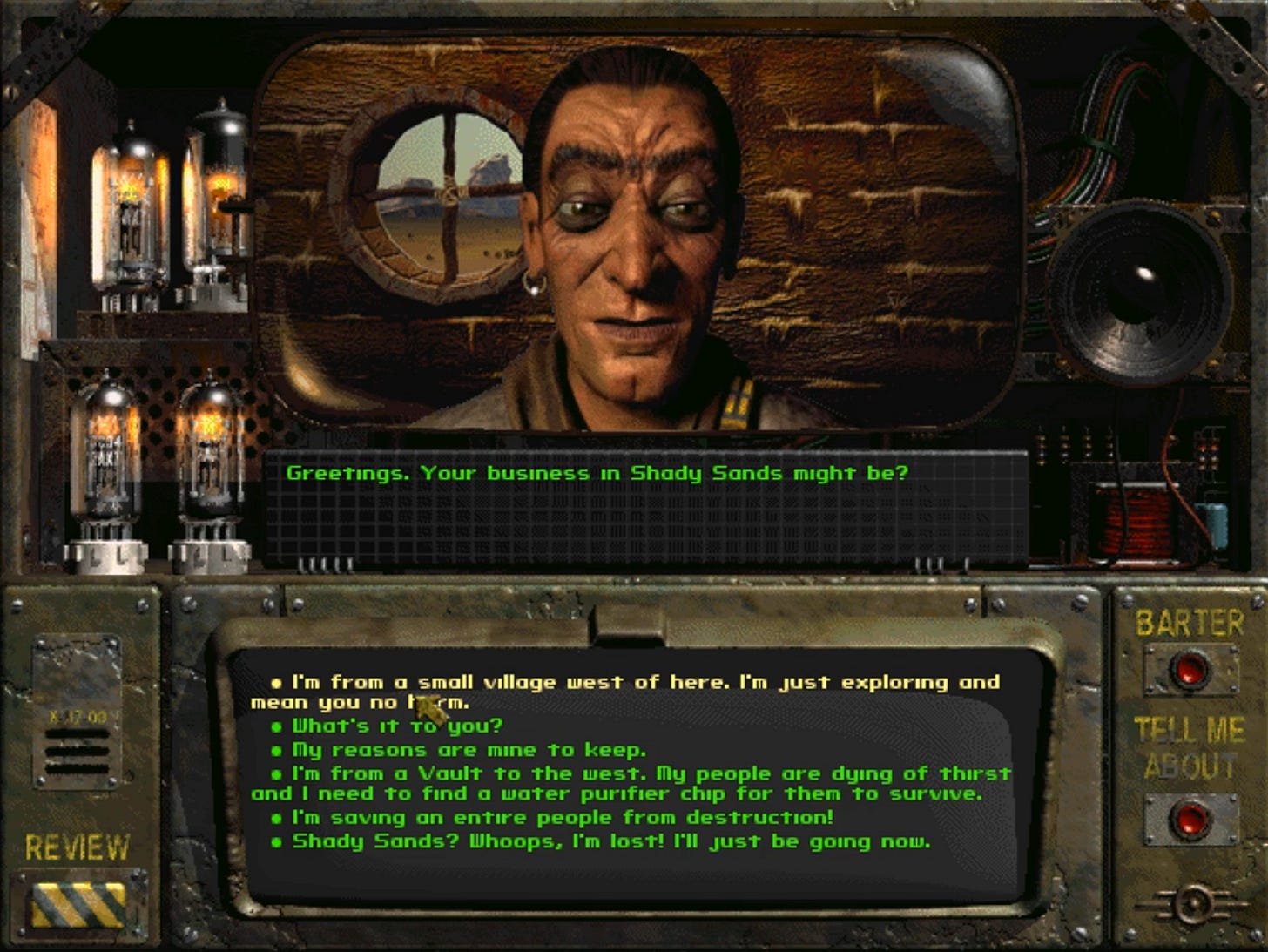

For my part, I journey eastward towards Vault 15, but tarry awhile when I encounter a walled settlement of hardy survivors who founded a relatively prosperous community among the ashes of civilization. “Welcome to Shady Sands, stranger,” says a modestly armed man as I approach the gate. “Please holster that weapon while you are here.” A welcome sight, especially compared to the bombed-out, rodent-infested husk that awaits me in Vault 15.

The venerable CRPG Book Project characterizes Fallout’s presentation as “sharply written with a dark, ironic optimism,” and I think that’s a pretty excellent description of the game’s tone and general atmosphere. From my perspective, the central theme at the heart of every Fallout game is the conflict between man’s cooperative, social nature and his proclivity towards domination. Civilization has been destroyed in nuclear fire. How can we rebuild without regressing into the same cycles of conflict and violence that brought us here in the first place? Every major faction in the franchise has its own interpretation. Should we bioengineer our racial and ethnic divisions out of the genome? Embrace our differences and have another go at liberal democracy? Subjugate or outright slaughter all those who are weaker than us? Something else entirely? The best Fallout games give their players many opportunities to insert themselves into the debate, but there’s a reason why so many of them begin with a narration of the words “War never changes.”

Shady Sands, the progenitor of the New California Republic from later games, falls squarely into the “embrace our differences” camp. Glad for a warm welcome, I help them out by gunning down a bunch of gigantic, mutated scorpions occupying a nearby cave in return for a heap of character XP. Then I pay my respects and depart, making a brief detour to the now-derelict Vault 15 where I find a few supplies, a shitload of rats, and no water chip. So, I follow a rumor about a major trading city to the south where might be found a water chip. Called the Hub, it turns out to be a vast sprawl of ramshackle merchant operations amongst the occasional brick-and-mortar dwelling occupied by the wealthy and influential. Very much a libertarian vibe, but most of its people are just ordinary survivors with ordinary problems who are happy to trade goods and rumors, and particularly so with anyone who helps them out.

THE MEANING OF “PLAYER AGENCY”

A lot of gamers purport to want agency in their RPGs, but what precisely constitutes that agency is usually left unspecified. We often think of “player agency” as meaning something to the effect of “the player has a lot of options at their disposal.” In practice, this usually means that the player forks a story by selecting one dialogue option over another. That’s certainly part of the equation, but it’s too reductive as a catch-all definition. I think a better interpretation is that players express agency over a game when their own imaginations and decision-making faculties are the primary drivers of the experience. Designing RPG narratives like this is how you end up with choicey-consequencey games that empower players to tell their own stories rather than glorified choose-your-own-adventures whose incidental plot elements are revealed or ignored based on your selections in a dialogue interface.

Fallout’s own handling of dialogue is deservedly famous for both its efficient brevity and its surprising flexibility. Unlike most modern RPGs, Fallout will often quietly insert extra dialogue choices into the list of options if the player meets the requisite Speech skill threshold. It’s then up to players themselves to apply their own intellects and social intuitions to actually make use of the skill. This makes it dramatically easier to roleplay both diplomatic characters and the socially inept — you seldom feel like you’re being railroaded into an obviously correct choice or being arbitrarily prevented from doing so. Speech in classic Fallout lets you insert yourself into the game’s fiction without becoming a cheat that the game gives you and encourages you to use.

Compared especially to the standard that grew popular in Fallout 3’s diluvian wake, the classic Fallout games put an extraordinary amount of trust in the player. My time in the Hub really stuck out as an example in this most recent playthrough. You can find a lead on a water chip by inquiring of the settlement’s more worldly merchants, but you won’t want to follow it before you’re geared up. Weapons, armor, and healing supplies — particularly those at the higher tiers — are extremely expensive, and you’re a broke wanderer. There’s a ton of money to be earned or expropriated in the Hub, but it’s on you to figure out what options are available to your character and how far you’re willing to push your morals to take advantage of them. And don’t forget: you’ve been traveling for a few weeks at this point, and Vault 13’s water supply continues to dwindle.

For my part, I meet the head of a trading company whose caravans keep mysteriously disappearing in the wastes. My investigation leads me to the abode of the series’ famous Deathclaw, a mutated reptile much taller than a man with sword-like talons and a tough hide that my early-game firearms struggle to pierce. But I’m a good enough shot by now to reliably target individual body parts, and its eyes are as squishy and penetrable as one would expect. In the heart of its cave, an eight-foot-tall man with pale-green skin and elephantine musculature lays dying. A data tape on his person reveals that whole legions of mutants like him are terrorizing the wastes, attacking caravans and kidnapping the “normals” for reasons unspecified. Guess the borked water chip is just about the least of Vault 13’s problems.

Nevertheless, I get another lead on a chip from a Hub resident who’s grateful for my warning, if not for the chaos it presages. I embark from the Hub towards the aptly named city of Necropolis, inhabited solely by ghoulish survivors whose forms are twisted and decrepit from prolonged exposure to nuclear radiation. Most are shambling husks without discernible humanity. But as I wander the sewers, I encounter a camp of them whose leader addresses me with peaceful overtures.

CREATIVE PASSION FOR ITS OWN SAKE

A recurring theme among older RPGs is that their limited audiences and commensurately lower budgets made room for more creative latitude in their designs than we’ve come to expect from the obsessively growth-oriented industry of today. They could take risks, experiment with bizarre ideas, and otherwise push the envelope in ways that are sharply restricted by the modern industry’s huge investments and long development cycles.

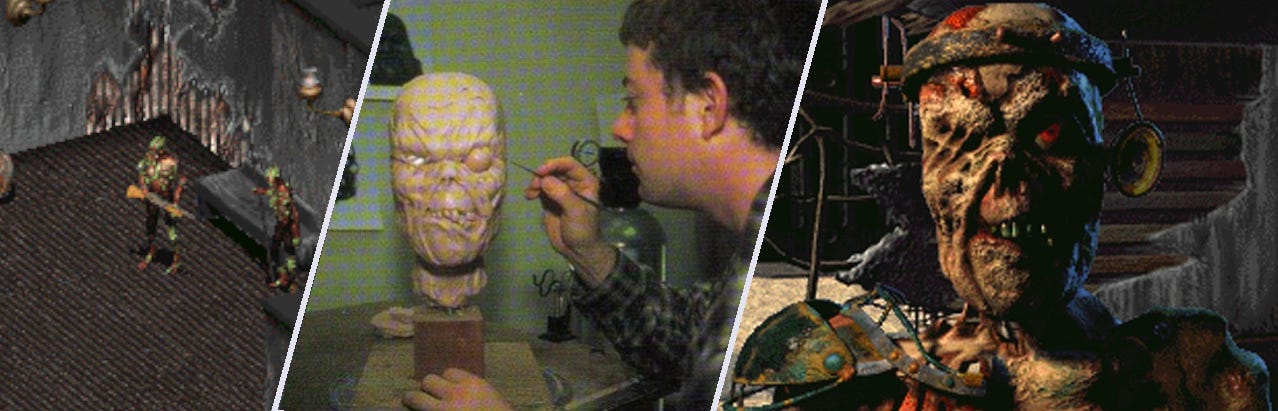

Classic Fallout exemplifies too many instances of this to count, but my sentimental favorite has got to be the Talking Heads. These games had 2D sprite graphics that’re readable, evocative, and still hold up well. But the character sprites, lacking faces or emotive animations, couldn’t really sell the games’ most narratively important characters or the excellent work of the voice cast on their own. Not wanting to exacerbate the problem with nineties-era 3D or to add thousands of development hours by painstakingly animating faces, the team met the problem in the middle with an innovative approach to character animation that hybridized computer graphics with meatspace sculpture. Here, look:

Of course, these work best when you see them in action. My hot take is that the Talking Heads from classic Fallout look better and convey more personality than any of the fully animated models from the entire library of 3D Fallout games that followed. And while I’m at it, another word on the 2D spritework. The effort and talent on display with damn near every sprite in these games is astonishing for the era. They don’t always reach the ceilings of immersively desolate atmosphere that their 3D descendants occasionally hit, but I reckon their floors are much higher. Plus, the technical simplicity that this style affords relative to 3D environments pays dividends in development efficiency — an entire settlement can be visually conveyed to a player with just a few dozen assets. This is a large part of the reason why Fallout 2 could be made in less than a year despite the tremendous scale of its world, and it’s also why the independent creators of today can make fan-games that compete with the OGs without salaried teams or ageless development cycles. More on that next week.

The ghoul in the Necropolis sewers explains that, because their water pump is broken, the city’s drinking water is purified by a fully functional water chip. He begs me not to take it unless I can repair the pump. The chip is elsewhere, practically unguarded, and I could easily seize it and leave the poor wretches to their fate. But I’m clever enough to execute most mechanical repairs and would rather not gain a reputation for dooming an entire people, so I emerge from the sewers and head for the warehouse containing the broken water pump. A team of mutants stops me at the door. Their horrifically mutated leader, intellectually handicapped by whichever process made him so, grunts an explanation of his orders: refuse entry to and take custody of any normals.

“But I’m not a normal!” I exclaim in protest.

“Harry confused. You not ghoul. You not normal. Hmm, what you?” he mumbles.

“I’m a highly advanced robot,” I confabulate. Fortunately, the Speech dice roll in my favor.

“OK. Go now. Gotta keep eyes out for humans. Not have time for you.”

The water pump is easily repaired in the warehouse beyond. I hear the pump whir to life as I yank the water chip from the mainframe in which it’s socketed. A few months have passed since I left Vault 13 in search of it, but I’ll now be able to return with plenty of time to spare. However, in light of the past week’s events, it’s apparent that the Vault is still in danger. And indeed, the overseer has a new job for me almost as soon as the water purification system successfully reboots.

“The mutant population is far greater than could be expected by natural growth or mutations… someone’s generating new mutants,” he explains. There must be some kind of fearsome, eldritch lab hidden somewhere in the wastes. “As long as someone is creating hostile mutants at this rate, the Vault’s safety is at stake! Find and destroy this lab as soon as you can.”

...and again, that’s quite literally all of the direction you’re given. The game ends after you permanently stop the deliberate generation of new mutants. But you still have to figure out what’s creating them, who’s responsible, where they’re at, and how on earth you intend to stop them. After starting and completing an entire hero’s journey, you’ve still got well over half of the game to go.

WAR CHANGES AFTER ALL

Fallout isn’t a perfect game by any means, but its legacy endures for good reason and it absolutely deserves to be counted among the greatest computer RPGs of all time. Imitated by many but replicated by none, it proudly elevated artistry and thoughtfulness as core pillars of its design. These days, it remains a precious artifact of the medium and a must-play for any serious observer of gaming’s cultural evolution. It drips with humanity even while awash in the current of its witty satire, and it offers a thought-provoking perspective on the franchise’s now-mainstream setting that fans of the latter 3D Fallouts will love to death. I can’t recommend it, or its sequel, highly enough.

If indeed you entertain an interest in trying the classic Fallout games, I’m glad to report that you’re in luck. They’re sold on Steam and GOG for $10 each, or for a fistful of pocket change on sale. Thanks to modern compatibility layers, they both run out-of-the-box on contemporary systems. I must say, it was quite a trip to see a CRPG from 1997 run flawlessly on my Linux machine with absolutely zero adjustment or configuration. By the way, both Fallouts 1 and 2 are quite manageably brief by modern standards. In particular, you can expect your first full playthrough of Fallout 1 to take less than twenty hours in total.

Classic Fallout may never have been replicated by any official installment of the franchise it created, but rumors of its demise are severely exaggerated. Since at least 2013, there has existed a small but healthy culture of craft RPG design that uses Fallout 2’s engine to create entirely original games both within and beyond Fallout’s fictional universe. These are noncommercial projects made by very small teams of extremely passionate fans, and they represent some of the best and noblest of what independent game design has to offer. As a matter of fact, I’d say at least a couple of them compete with Interplay’s standard of quality. That’ll be our topic for next week — get yourself Subscribed if you haven’t already so that ya don’t miss it.

By “classic Fallout,” I mean the two Interplay-published games from 1997 and 1998. Some folks include Fallout Tactics as well, but I think of that one as a totally different beast.

Aside from Fallout 2, I could only come up with a couple: Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura and ATOM RPG. Let me know if you can think of any others.

For the uninitiated: Strength, Perception, Endurance, Charisma, Intelligence, Agility, and Luck. Most characters will pick one or two of the above in which to specialize and one or two in which to be deficient. Interplay originally planned on adapting GURPS, but the licensors got cold feet when they saw how violent FO1 was going to be.

As bad as the Fall from Morrowind to Oblivion was, it was nowhere near as shameful as the utter collapse from Fallout 2 to 3.

Several thoughts:

I played Fallout when it came out. I vividly remember one quest in the Hub where a crime lord offers an absurd number of caps to massacre a church with no witnesses.

The first time I did it, I focused on the guards and the little boy at the door ran away, and I didn't get paid because there was a witness.

I loaded the game and then started with the little boy, and was awarded the reputation "Child Killer" which I didn't want, so I loaded the game and turned the crime lord into the sheriff.

That was masterful game design, it was a real consequence for your actions. The game didn't stop you from doing it, but did make you live with it.

I also played Fallout 3 when it came out, and bounced off of it HARD.

One of the things I loved about the first two fallout games is the 2d design suggested a much larger world then what you saw. So for example, the Hub had a few areas, but the edges of the areas suggested there were more parts of the Hub, they just weren't relevant for you. It made the world seem much larger. Another example, is in Fallout 2, almost the entirety of the New California Republic is off the edge of the game map. You are playing a sliver of a much larger world.

By comparison, Fallout 3, New Vegas, and 4, render the entire community. It makes the world seem so small. In Fallout 4, the largest community is in Fenway, and there are maybe 50 people in it. Higher fidelity makes the world seem so small.

Junktown lives rent free in my head nearly 30 years later.