Let's Have More Scalp-Camera Gameplay

Hotline Miami, Darkwood, and the esoteric wisdom of the human scalp

INTRO: “SCALP-CAMERA?” WHAT THE HELL IS HE TALKING ABOUT?

I’m glad you asked! Short answer: I’ve got a peculiar bone to pick with contemporary video gaming discourse.

Consider: when you think of the phrase “top-down perspective” as it applies to game design, what sort of camera angle(s) come to mind? I was pondering this myself while perusing Steam’s list of hottest-selling “top-down” games, which suggests that the popular answer is a noncommittal shrug. At time of writing, the Top Five includes two games with fixed isometric1 perspectives and two games with variable perspective, with the new Door Kickers sequel rounding them out. Is “camera higher than shoulder-level” really the only criterion defining the top-down perspective?

Look, I have no background whatsoever in the theory of 2D projection, so take this with a grain of salt. But my intuition of the term “top-down” suggests a camera angle perpendicular to the ground. By my estimation, then, Door Kickers 2 is the true ambassador of top-down games among those five. All the others either have user-adjustable cameras or else what most video gaming correspondents would call “isometric,” i.e., cameras at some kind of angled perspective high above the ground. I say we need a revised taxonomy for “strictly top-down” games like Door Kickers, which I will henceforth refer to as “scalp-camera”2 games. Scalps are what the camera’s always pointing at, and we’ve got to start somewhere.

After all, Steam’s “top-down” designation now gleefully lists Company of Heroes 3 and Tiny Glade under the selfsame vertical, like shelving E. L. James alongside the Kama Sutra. Barnes & Noble never pulled that shit, so why should the video gaming public have to settle for such imprecision? As my example hopefully illustrates, I think the industry at large has paid bizarrely little attention to this distinction, and that’s too bad — there are gameplay experiences unique to the scalp-focused camera perspective that I think are still under-explored.

I’d like to talk this week about my two favorite scalp-cam games, and about why the scalp-focused perspective is crucial to their respective appeals. I also want to discuss where I see that underutilized potential in the concept, which I’ll use as an excuse to presage a fun little project of mine. This newsletter will be a good bit shorter than our first four, largely because Substack keeps insisting that they’re too long for email delivery. Let me know how you like this shorter format if it makes any difference to you, and I’ll continue advancing the dialectic until we find the sweet spot. Right, now I’ll get on with it.

FLOORPLAN’S INHUMANITY TO MAN

My two favorite scalp-cam games are 2012’s Hotline Miami and 2017’s Darkwood, which I think can both fairly be characterized as cult hits or better now that we’re several years removed from their initial releases. I’ll begin by telling you about what they each achieve with the scalp-camera perspective, and I’ll include a little background information for the benefit of readers who haven’t played several thousand video games over nearly thirty years.

HOTLINE MIAMI: QUICK, AIM AT THE SCALPS!

Hotline Miami is a game about… actually, it was never all that obvious even after several playthroughs. What’s clear is that you play as a nameless hitman in 1980s Miami who slays many hundreds of bald Russian gangsters at the instruction of his answering machine, completely zooted off psychedelics and stimulant narcotics all the while — as I say, it takes place in 1980s Miami. Among its most recognizable gameplay mechanics is the rich selection of rubber animal masks that the protagonist can collect and equip, each activating a unique gameplay effect. That’s right: covering the protagonist’s face is the job of the camera and the secondary gameplay loop.

The main protagonist of Hotline Miami is minimally characterized, but he’s more than just a cipher. He undertakes over a dozen missions in which he usually commits to the wholesale slaughter of everyone on-scene, never with any particular awareness of what he’s doing or why he’s going to all the trouble. I’m put in a mind of Hitman’s Agent 47 by way of Henry from Eraserhead, which goes great lengths toward reinforcing the heart-pounding catharsis of the combat mechanics. I argue that this amusingly depersonalizing effect simply wouldn’t work with any other camera perspective.

In fact, since depersonalization is a central theme of the game’s narrative, I’d say the scalp-cam perspective is straight-up irreplaceable. The one-hit deaths and instantaneous retries also contribute to a derealized atmosphere, but Super Meat Boy had those very same mechanics and didn’t feel remotely evocative of a drug-fueled Miami bloodbath — what gives? I really think it comes down to staring at the protagonist’s rubber-clad scalp all game long.

Seriously, look again at the screenshot above and try to imagine how it’d play with an isometric perspective such that you could see the protagonist’s face whenever. Or, wait — you don’t even need to imagine, because we already got that in 2017’s Ruiner, for which Hotline Miami was a direct inspiration. In forsaking its protagonist’s scalp and the depersonalization that comes with it, Ruiner had to make a difficult choice: humanize the protagonist and ruin the carefully orchestrated psychological distance, or just forget all about it and double down with a cartoonish parody of Hotline Miami’s already farcical violence. You’ll never guess which option they chose.

Hotline Miami’s use of scalp-cam works so well because players can easily lose themselves in the moment-to-moment catharsis without ever intuiting the protagonist’s motivations or humanizing him or his opponents, any of which would most likely dampen the appeal of serially perpetrating massacres. I’ll return to the theme of deliberate psychological distance in a moment — for now, let’s introduce my other favorite scalp-cam game.

DARKWOOD: NO, WAIT — RUN FROM THE SCALPS!

Darkwood is a game about the cruel realities of living as Eastern European rural peasantry. More specifically, it’s about the anonymous protagonist’s desperate struggle for survival in an arboreal hellscape that’s been corrupted by some eldritch monstrosity. It was accurately postured as a tense horror game without intentional jumpscares, and remains the only genuinely terrifying scalp-cam game to see a commercial release3.

Minor spoilers for Darkwood throughout the rest of this section. No judgement if you wanna skip ahead to the next section.

Like his counterpart in Hotline Miami, we know very little for certain about Darkwood’s protagonist other than that his psyche is chemically altered, although Darkwood expands on the theme by extending the alteration to his very physiology as the merciless Polish forest gradually consumes him. We see rare glimpses of his face, but only in heavily obscured stills that are used to punctuate story beats. By these means, Darkwood adopts Hotline Miami’s idea of deliberate psychological distance from the protagonist and then doubles down.

The other fascinating aspect of Darkwood’s horror is that it’s tense as hell even when you’re running through an open clearing. The scalp-cam perspective necessitates that the player can only ever see a few dozen feet in front of the protagonist’s face, which makes regularly checking one’s six and staying vigilant even more important.

Again, look at the screenshot above and imagine it at an oblique perspective such that both characters’ faces were plainly visible. Even if it wouldn’t make for a straight-up comical experience, it would vastly alter how Darkwood feels to play, and I think it would be dramatically less frightening. Naturally, a lanky monstrosity barreling toward you is all the spookier if you can’t quite make out its features. Darkwood understands this better than perhaps any other horror game since Amnesia: The Dark Descent, and gets legendary mileage out of it. The game stays scary even on repeat playthroughs when you know what to expect.

So, we’ve accounted for at least a few benefits with which the scalp-camera perspective can imbue a game, and I hypothesize that we can squeeze even more out of the idea.

UNSEEN FACES, UNSEEN POTENTIAL

Putting literal distance between the protagonist and the player in order to produce figurative distance between them is one thing, but what about the world beyond the protagonist’s head? Let’s ask ourselves: what is the most prominent functional difference between top-down/isometric gameplay and first-person or behind-the-shoulder gameplay? If you ask me, the clear answer is situational awareness. At a glance, one can discern far more information from a floorplan than from one’s narrow binocular vision.

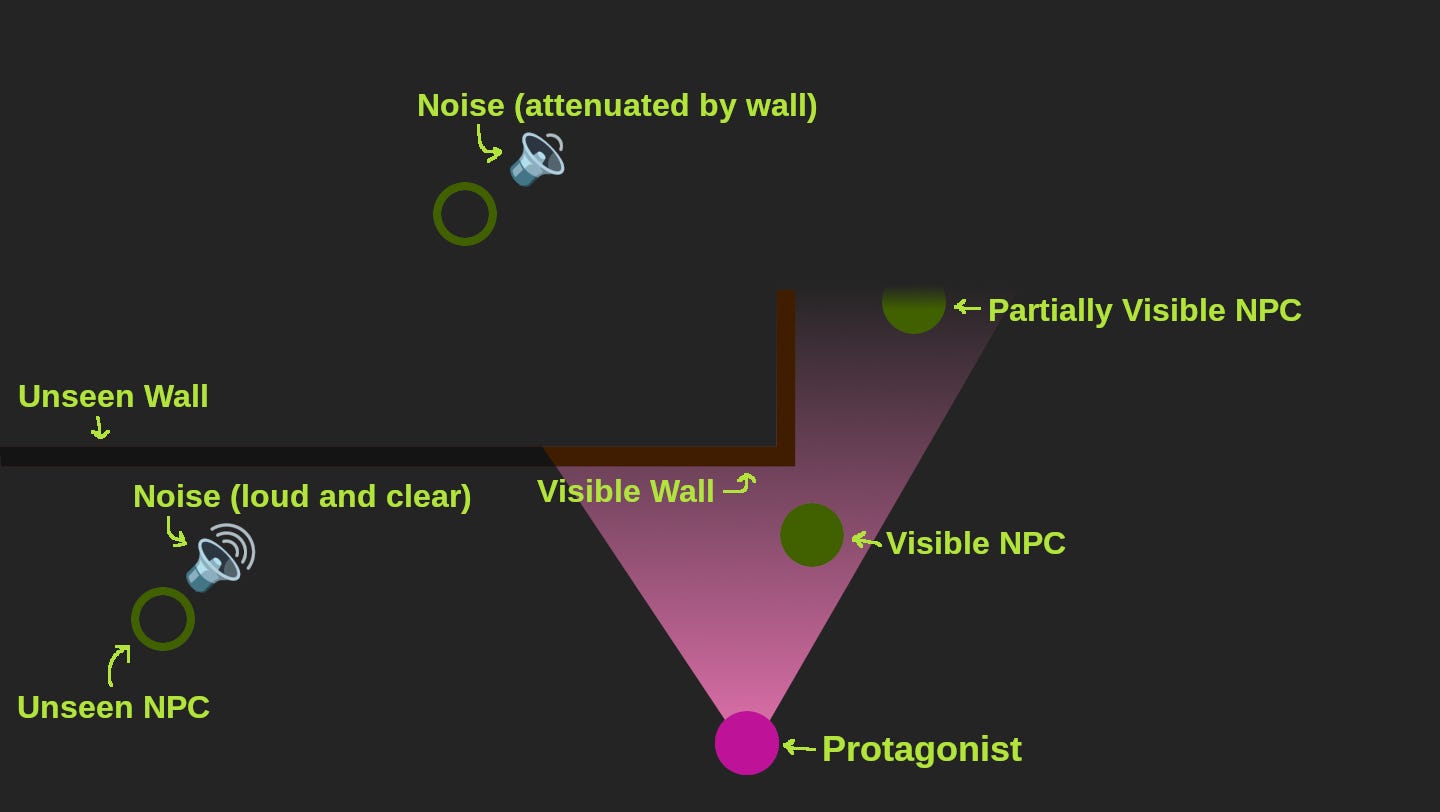

Hotline Miami accepts this at face-value and gives the player comprehensive visual information at almost all times. Darkwood twists the formula somewhat with its cone-of-vision mechanic that elides gameplay-critical details like enemies and pickups unless the protagonist is facing them, but otherwise retains the comparatively vast amount of environmental detail-per-frame. It compensates for the visual occlusion somewhat with the addition of spatial audio, such that the player can often estimate an unseen enemy’s location by paying attention to the noises it makes. From a gameplay perspective, I think there’s room to expand this concept further still.

Here’s the short version of what I have in mind: the high-level environmental surveying of Hotline Miami plus Darkwood’s emphasis on sensory limitations, with spatial audio upgraded to a core gameplay mechanic. Let me sketch out what I’m picturing…

You’ll be pleased to hear that I even have the germ of an idea for context to support it. How about this for an elevator pitch: it’s a scalp-cam game where you play as a security professional guarding valuables from the protagonist of an unrelated stealth game. That would offer a convenient narrative excuse to set the whole thing in pitch-darkness, as well as plenty of opportunities to create tension with an unfamiliar soundscape. It’s starting to sound like a horror game in the vein of Darkwood, but with a tighter primary gameplay loop and vastly different theming. That sounds like enough of a justification for a prototype!

UP NEXT

I retired from freelance Web development several months ago, so it’s been awhile since I programmed anything neat and I could really use the extra creative stimulus. Accordingly, I’m going to try to prototype the above idea to find out whether I’m onto something. I’ll let you know how it’s going in a couple of weeks — it’s been ages since I did any remotely serious game-dev, so I’m pretty excited to rediscover what the community is up to.

As for next week, you already know what’s coming if you’ve been diligently reading The Spieler over this past month. By the time this newsletter lands in your inbox, Psycho Patrol R will have been out in Early Access for a solid twenty-four hours and I should be thoroughly engrossed in worship. It will, appropriately enough, be the subject of our April 1st newsletter. And if it makes any difference to you, please do let me know how you like this shorter format and whether you think it could be improved with a higher or lower word-count.

I’ll be back on April Fool’s Day with my early impressions of Psycho Patrol R. It should be an orgone-huffing fuckfest of the first degree — hope to see you there!

Til next time friends <3

I’m reliably informed that most so-called “isometric” games actually use some kind of oblique projection, but there are enough semantic landmines in this newsletter as-is. I’ll carry on using the term “isometric” as most gamers do, with sincere apologies to any triggered architects or 2D artists who may be reading.

Credit to my wife for coming up with the word “scalp” to differentiate from more-popular 2D isometry. I can always count on her to fill in the gaps when I go off on these delirious tangents <3

The only other ones I can think of are Motte Island and Subterrain, but I think both play more like action games with horror theming than like outright horror games. Do let me know if you can think of any I missed!

Liked what I read, though I had to skip the Darkwood section because it's been on my short list for longer than I can remember. Wanted to mention my two favorite scalp-cams.

First, Notrium. This now-ancient game was one of the first true modern indies to catch my eye, and holds up as a surprisingly deep and complex survival-crafting-shooter-thing that really hasn't been emulated enough. You spend most of your time running out to grab bits of wreckage to turn into pipe shotguns and radar units, with your goal being one of a few ways of getting off the planet, including building a strong enough distress beacon or repairing an escape shuttle. Then there's alternate modes where you can play as an android, some kind of psychic alien, or one of the thinly veiled xenomorphs inhabiting the planet, all with their own playstyle and goals. And, importantly for this new genre, the completely perpendicular camera angle makes the action tense, the open-air scenery almost claustrophobic, and the visuals readable but still alien and off-putting.

The second, and maybe even more bizarre, Devil Slayer: Raksasi. It's a roguelite brawler that is much slower and more methodical than Hotline Miami on top of having downright gruesome gore, but it's also incredibly engrossing. There are a variety of characters to pick, all with their own abilities and starting weapons, and every weapon option feels completely different to wield, including having particular sweet spots that force you to manage your positioning and timing very precisely. It's also one of the few roguelites I've played where it feels like you genuinely have more control over your fate than the random number generator does, and it has some boss fights that are more tense than almost anything FromSoft has achieved. If you can get over some control frustrations and the fact that every death is punctuated by a giant splash screen of your heroine with her clothes mostly torn off, it's worth a play.

Honorable mention here for Cryptark, which despite being a more standard side-on perspective, I would argue captures a lot of what you seem to be grasping at in your attempt to canonize the scalp-cam. You start each raid with a full blueprint of the target derelict, and can plan out your attack by noting the entrances, major components, some of which are shielding or wired as alarms to other components, and others which can simplify other parts of your assault if you take them out, and all the enemy spawners, but once you launch, the whole thing plays out in real time as you struggle to actually hit your targets without getting bogged down by reinforcements. Again, the perspective means that despite having prior proper planning, you're still constantly getting jumped by things that, logically, your ship should have had vision on for a while, but as a player you're only noticing as it gets into firing range. I think it's a big part of why the developer's next game, which was basically a remake of Cryptark but in 3D, didn't succeed.

Finally, I'm curious if you've played Intravenous or its sequel. Like Darkwood, it's been sitting on my get-to pile for a while, and I've heard good things, especially now that the sequel has apparently applied some of it's quality of life adjustments to the first game's campaign.

Darkwood mentioned!! It's one of my favourite games ever, and certainly the most unique top-down I have seen. I loved that details in your peripheral appear not only obscured by shadows but actually 'wrong' in terms of detail, e.g. unseen building interiors tend to look much more orderly and less dilapidated than when you actually look at them. It's as if the protagonist is trying and failing to impose order on the chaos around him and make sense of things, proceeding with the assumptions of his former life.

Also liked your point about using the top-down method to create tension and maintain psychological distance between the player and the character, which was particularly suitable for Darkwood.