How Can We Design a Skyrim-Killer?

We already have the ingredients for the next billion-dollar RPG. Time to bring them all into one package.

ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT

Gosh, video games sure do take a long time to make these days. Believe it or not, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim — the best-selling RPG of all time, by most accounts — was released in 2011 after only three years in full development. Afterwards, it took Bethesda Game Studios nearly seven whole years just to announce another installment, and even that was only a teaser entirely devoid of context. It’s now been more than seven additional years since the as-yet-unsubtitled The Elder Scrolls VI was announced at E3 2018, and we’ve heard next to nothing about the project since. At this rate, we should be playing TES VI sometime late this decade, and can look forward to TES VII shortly after every star in the universe has gone dark.

In all seriousness, though, it’s apparent by now that a first-party successor to Skyrim is not in the cards anytime soon. I’ve got my fingers crossed into knots for the quality and success of TES VI, but they’ve been crossed for the better part of fifteen years now and my joints are starting to ache. Besides, the triple-A games industry in general and Microsoft’s hypercorporate death machine in particular are in such dire straits right now that a worthy follow-up to any historically significant title seems far-fetched, let alone what is possibly the most beloved RPG ever made in Skyrim. I’d love to be proven wrong but, frankly, a promising trailer for TES VI would be extremely surprising at this juncture. I’d sooner expect to hear that the next Elder Scrolls game will be a multiplayer extraction shooter complete with a DLC pass and a licensing deal with Roblox.

My point is that those of us who value this flavor of game design need to do some serious thinking about where the Grand RPG1 goes from here. The Oblivion remaster’s success is certainly welcome, but it underscores how the greater industry remains trapped in a holding pattern of mid-budget re-releases and high-profile catastrophes while the sub-triple-A sector eats its lunch. All of this was forcefully and unambiguously evidenced by the remarkable buzz around Tainted Grail: The Fall of Avalon recently, which also took me by surprise. But for as much as said newcomer impresses me, I don’t think it’s the Skyrim-killer we’ve been anticipating for nigh on fifteen years.

That’s mostly because, for all the skill and ambition on display, its aura is that of a mid-budget Skyrim-like and it has no particularly strong identity of its own beyond the admittedly very intriguing setting and art direction. Those are certainly necessary elements in any Grand RPG that makes pretense to compete with the genre’s greatest, but they’re far from sufficient on their own. Sooner or later, we’ll need to aim higher than we did in 2011: I watch gameplay footage of Tainted Grail’s tutorial dungeon, and my jaw literally drops when I see two chthonic giants pushing a massive Conan’s Wheel toward unimaginable ends. Then I see that the lockpicking minigame is a direct copy of Skyrim’s version from nearly fifteen years ago, and I heave a long, weary sigh.

In the wake of our jolly adventure to Tamriel Rebuilt’s biggest city (so far) last week, I promised we’d talk more about why I reckon Morrowind holds the keys to advancing the RPG dialectic. To clarify, though, it isn’t as simple as just reproducing its mechanics on a modern engine with fancier graphics. But that doesn’t mean we can’t still reach for low-hanging fruit — no game of this kind has yet combined all the genre’s best ideas into a single package, and I think pulling that off is the most straightforward route to finally overcoming Skyrim and beginning a new era for the genre.

Obviously, the set of “best” ideas in a given Bethesda-style RPG will differ considerably between players. But as long as we can agree on the general character of our intended experience, i.e., the mechanical facilitation of a player-driven adventure through a thoughtfully designed world, then it should be easy enough to determine which parts do and don’t meaningfully contribute to that experience. Let’s begin with the world itself, and then we can drill down into how the player interacts with it in ground-level gameplay.

A WORLD WORTH DISCOVERING

When we were talking about Morrowind’s excellent and somehow-still-evolving world in last week’s newsletter, I mentioned that one of the biggest casualties between Morrowind and Oblivion was the immersive travel. To quickly recap: in Morrowind, unless you have magical aid or can use public transit, you go everywhere on foot, period. In Oblivion and beyond, you can just teleport to any previously discovered point of interest at no material cost other than time. The reasons why I prefer the former system are simple: it keeps you engaged with the world at all times, and the world can continue to challenge and provoke you even deep into your campaigns.

One of the amazing things about Morrowind’s world design — and one of the reasons why the game remains so popular to this day — is that it feels naturalistic and lived-in despite a relative lack of true reactivity. You feel it from the very first quest in the game, when you’re told to find your way to Balmora but don’t have so much as a roadmap to get you there. Instead of following a quest compass or orienteering with a painterly world map, you just… walk in the approximate cardinal direction of your destination, orienting yourself with landmarks and road signs along the way. You know, like a real-life fantasy adventurer would!

And as you travel those roads and see those landmarks on the horizon, your brain is inclined to treat them as actual markers of civilization rather than tools added by a level designer for your convenience as a player. This is the sort of trick that I think people are referring to when they talk about “Bethesda Magic” — objectively speaking, the roads and navigational aids are there exclusively for your convenience as a player, but they feel like they could have emerged naturally from the pilgrimage routes and mercantile enterprises that you learn about throughout the game. It’s my opinion that this sensation simply didn’t translate to Oblivion or Skyrim, and I’m pretty sure it’s because both of those games sharply deemphasized inter-quest travel as a core adventuring mechanic.

That all said, this is an essay about selecting the best from both worlds, so let me give credit where it’s due. Skyrim made some real strides with its world design by bringing altitude into the equation, and I want more of that. One thing I unmixedly love about TES V’s realization of Skyrim is the sense of majesty you get from climbing a tall peak and looking down onto the world below, including places you’ve recently been or to which you’ll soon venture. The actual process of climbing may be a pain in the ass, and there may be precious few reasons to bother in the first place, but the effect it achieves is undeniably special when it works. Besides, we can easily improve upon it. Why not scatter a handful of lairs and monasteries among the peaks to give us something worth finding? Why not throw in some simple mountaineering mechanics to make the journey up there more compelling?

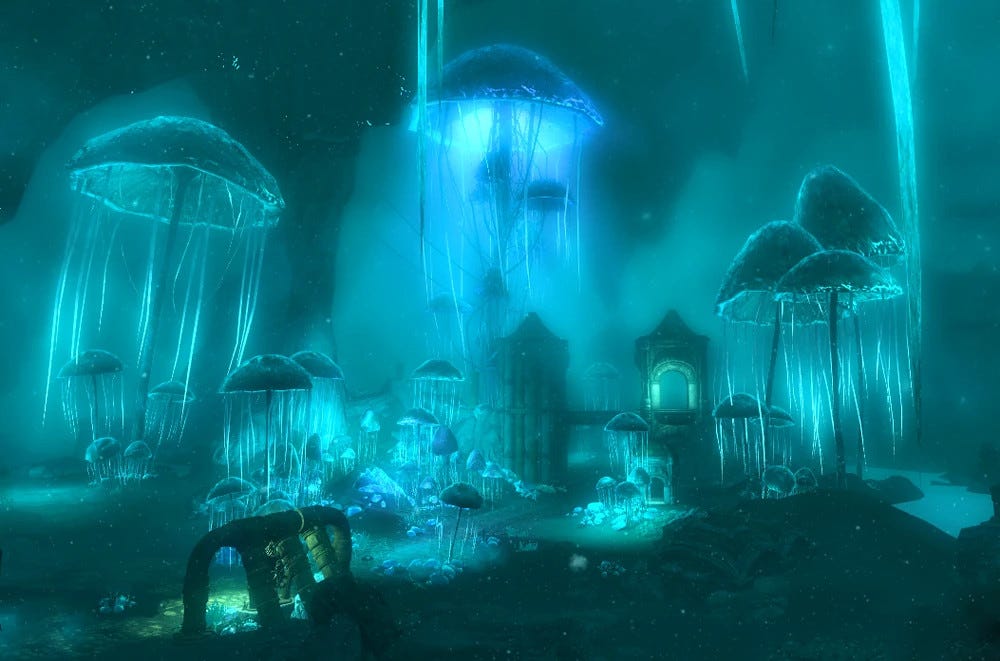

On the other side of the altimeter, I’ve always admired Skyrim’s Blackreach region, too. In case you’re unfamiliar, Blackreach is a colossal subterranean cavern with its own ecosystem of non-photosynthesizing flora and troglodytic fauna. It’s my understanding that the original plan was to use these subterranean passages to connect much of the overworld, which would’ve kicked ass had the idea not been cut during production. Still, Blackreach is a great addition to the Grand RPG formula because it justifies a totally different environment from the overworld, ripe for entirely novel discovery. The Oblivion gates in TES IV served a similar purpose by essentially adding literal Hell as a playable environment. The lessons to take away are that we don’t need to constrain ourselves to strictly thematic biomes, and that adventuring gameplay benefits from a wide variety of environs to traverse and exploit.

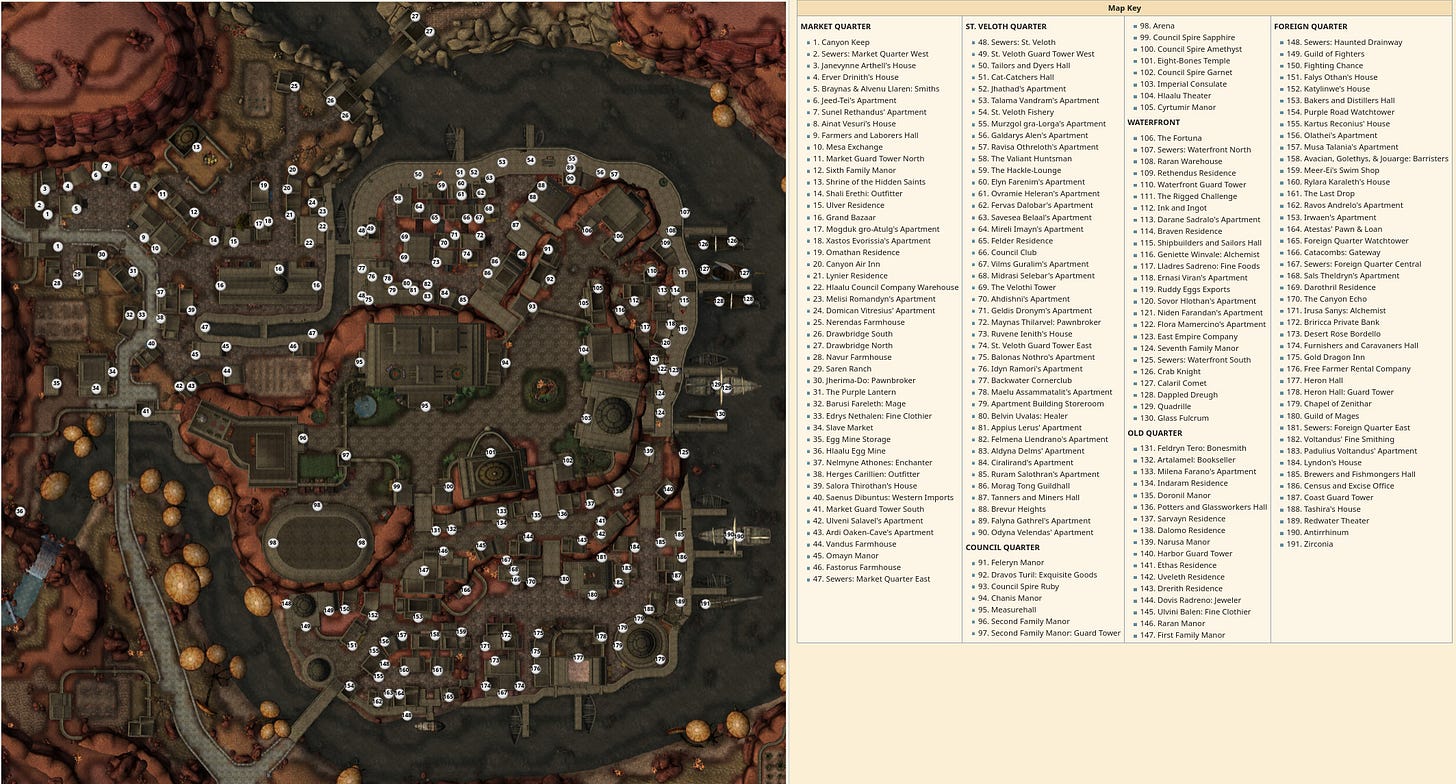

Finally, I have to talk about how these games handle civilized settlements. It’s well understood by now that Skyrim’s villages and cities are almost cartoonishly small relative to our expectations of civilization because the game had to run on seventh-generation console hardware and there was just no better way to compromise under the circumstances. Starfield was roundly criticized for its expansive yet barren “main” city, suggesting that trading verisimilitude for size isn’t the right way to improve upon that compromise. If you read my account from last week, you can probably guess at where I locate the sweet spot.

The short version is that Morrowind modders are pretty much nailing the concept of city-as-adventure-hook even as we speak. In the time since my trip to Narsis last week, I’ve also had time to check out Project Cyrodiil, which at time of writing includes a positively astonishing realization of the Imperial city of Anvil after an old-lore reinterpretation. I still need to play more of it and it’s a bit early to pass final judgement, but I think this might be the single most engrossing urban location I’ve ever explored in a video game. The greatness is once again in the details. The city hosts the usual complement of weaponsmiths and potion-sellers, but also some more grounded destinations like clothiers and art studios. There are extensive and well-differentiated neighborhoods, each with unique character. Locals and tourists stroll under grand stucco architecture and dine al-fresco alongside the canal. It feels remarkably similar to exploring a new city in real life, and that’s the Magic in action — no Bethesda necessary.

If we compare Narsis or Anvil to the capital of Skyrim in TES V, the difference is night-and-day. Games like Cyberpunk 2077 have long since established that dense and involved settlements are possible on modern hardware with cutting-edge graphical presentation, and the medieval fantasy environs of The Elder Scrolls et al. allow us to optimize the density/fidelity curve at a smaller scale and at a concordantly lower production cost. All the pieces are on the board, in other words. We just need someone to bring them all together at once, and to give the player lots of tools for manipulating them.

BEYOND DUNGEONEERING

Historically, even the biggest and most ambitious Grand RPGs have been very dungeon-focused in their world design and gameplay direction. By “dungeon,” I generically mean “enclosed level with treasures protected by puzzles and/or hostile creatures,” which may or may not be a literal dungeon in practice. This has been true of CRPGs since their earliest days, back when they were alternately called “dungeon crawlers” instead of roleplaying games. It’s a well-worn and popular strategy for facilitating an adventure, and for good reason — anybody, even someone who’s never played an RPG before, can intuitively understand the appeal of delving into forgotten chambers in search of wealth and glory. It’s a cornerstone of Western fantasy, and tends to motivate most of the journeying that takes place in open-world RPGs even in non-fantastical settings.

That said, there’s vastly more to adventuring than just dungeoneering alone, and I often get the impression that RPG systems are overtuned to the dungeon-looting aspect of the experience. We can again look to Morrowind for an example of a main questline in which dungeon-delving is relatively deemphasized: you still clear a number of dungeons in the course of a Morrowind playthrough but, in contrast with later titles, hardly any of them are mandatory for finishing the main quest. Much of its latter half consists instead of politicking and legend-building in order to lay the groundwork for the battle at the end. Skyrim makes noises in this direction with its civil war quests and that one twenty-minute sequence where you listen to a gaggle of belligerent assholes shout at each other around a boardroom table, but I’ve never met anyone who remembered those parts fondly, and I’m sure we can do better.

Let me give you an example of what I mean. It always felt strange that I can build a character in Skyrim with mastery of Illusion magic who can effortlessly manipulate the minds of his enemies, because there’s a cognitive dissonance that emerges when you start to think about the implications. Why is the arcane mastery of psychological manipulation only useful in combat? There’s so much more you could do with a system like that, and at relatively little additional development cost. I should be able to use Illusion magic toward adventurous ends like getting better prices from merchants or for making cops look the other way after I shank a local powerbroker. Even in Morrowind, I can cast a spell on a merchant or quest NPC to maximize their disposition if I have the foresight to create such a spell.2 What ever happened to that?

And while we’re on the subject, what happened to spellcrafting?3 I think it’s fair to say that it was one of the most standout features in each of TESes II through IV, so its absence in Skyrim was conspicuous. My superficial understanding of the matter is that the design team didn’t want players cheesing the quests with ultra-powerful spell effects like teleportation and health absorption. The reason I find this so confusing is that the previous games are some of the most cheeseable RPGs on the planet thanks to the addition of spellcrafting, and that’s part of what we all love about them. But the main reason why spellcrafting resonates is that it gives players an effectively infinite groundspring of tools for engaging with the world and even with their characters. I could wax poetic for hours about how much I miss this-or-that traversal spell when I’m wandering the lush valleys and snowcapped peaks of Skyrim, but suffice it to say just this much: wouldn’t Skyrim be, like, a hundred times more fun with levitation and the Boots of Blinding Speed added back in?4

I could come up with similar examples for all sorts of mechanics, and I imagine you could, too (I’d love to hear about it in the comments if anything comes to mind, by the way). My overarching point is that the next great RPG doesn’t need a sprawling narrative like The Witcher 3 or a farcically large playspace like Starfield in order to compete at the highest level. It just needs to reinforce the magic inherent to an adventure through a fantastical and unfamiliar world, and that takes place at the level of systems and mechanics. In other words, big worlds are less important than rich worlds, and the surest path to creating the latter is to facilitate many different ways of interacting with it.

SEIZING THE MEANS OF BETHESDA MAGIC

The real world is in its nightmare era lately, so I guess it’s really no surprise that millions of gamers are champing at the bit for some old-fashioned Bethesda-style escapism. That said, I can’t help but feel a little disappointed that the most prominent vehicles for that brand of escapism right now are a remaster of a nineteen-year-old game in the Oblivion remaster and a derivative of a fourteen-year-old game in Tainted Grail. RPG design has come so far since 2006 and 2011, and I think gamers both expect and deserve better.

Now, I don’t want to complain too much, because it’s not like there’s been a dearth of high-quality RPG design these past few years. It’s just that almost all of it has come from volunteers and unpaid hobbyists in the modding scene. I’ve already gushed enough about Tamriel Rebuilt and Project Tamriel for now. But I haven’t even mentioned full-fledged indie RPGs like Nehrim and Enderal, which are free mods for Oblivion and Skyrim that show off their own evolutions of the Western RPG tradition. Thing is, we’ve got a whole-ass commercial gaming industry that you’d think would be leading the charge, and it simply isn’t. Unless we’re planning on reorganizing society such that passionate fans can work full-time on these projects and eventually replace the professional industry in its capacity as foremost innovator, then we’ll have to fight for a professional industry that rewards innovation instead of bland conformity.

Can we count on Bethesda Game Studios to reverse its downward trajectory and come back with a generationally beloved successor to Skyrim in the form of TES VI? To be honest with you, I have no idea. I certainly don’t think we can count on such a thing anytime soon, though, and I’d like to see more competition in any case. So instead of waiting for BGS to get its act together and put out another great RPG, let’s make a point of identifying the sources of its success and propagating them throughout the medium.

My theory of the so-called Bethesda Magic is ultimately quite straightforward: Bethesda’s open-world RPGs capture such large and diverse audiences because, more than any other style of video game, they nourish our primordial instincts toward discovering and overcoming our environments. To me, Grand RPGs are best understood as adventure simulators, and that’s where I locate their core appeal. We’re an adventurous species by our very nature — it’s the reason why our ancestors crossed land bridges and ice shelves to migrate between continents instead of just hanging around in Africa these past two million years.

So, then, how do we design a Skyrim-killer? The short answer is that we stop designing RPGs around repetitive gear-grinds and numbing quest loops and start designing them around the inherently compelling aspects of adventure. Morrowind proved it was possible, Oblivion proved it could be commercially dominant, and Skyrim proved it could hold folks’ attention for well over a decade. But despite sharing a genre, all three of these games have a distinct character of their own borne of their particular worlds and the mechanical toolsets for engaging with them. We’re still waiting for a game that combines all their great ideas into one legendary package.

I have limited confidence in Bethesda’s ability to deliver such a thing anytime soon, but I feel unusually sanguine about that realization. After all, contemporary modding projects for Morrowind are absolutely washing a lot of recent triple-A RPGs, and those are free mods made by volunteers without strong industry connections or significant institutional support. It may be that this is the future of the medium, but I can’t help but wonder what we could achieve if only the professional industry would take a chance on a project built to stimulate the imagination instead of suppressing it. Until then, though, the free projects haven’t gone anywhere, and our cup yet runneth over. We’ll succeed in the end.

Til next time <3

Thanks for reading to the end! What are the most important elements of a great RPG by your estimation? Can you think of any ideas from other (sub)genres that’d be worth bringing into the fold? Tell me about it below!

I think the term “Grand RPG” was originally coined to describe the maybe-still-forthcoming Wayward Realms, but I use it to refer to the Bethesda-style open-world RPG of the Western tradition in general so that I don’t have to keep writing “Bethesda-style open-world RPG of the Western tradition.”

I learned just this year that Skyrim actually does have a disposition system, but it’s almost entirely vestigial and only ever indirectly player-facing. Go figure.

For the uninitiated: Morrowind and Oblivion both allow the player to combine discrete spell effects into their own custom spells or imbued into enchanted items. Skyrim dropped this feature entirely, alongside a number of said spell effects.

I suspect there are engine limitations in Skyrim’s specific case but, again, those were limitations from three console generations ago.

Great article. A few things I'd note:

From recent experience, it seems to me that there actually kind of was a great Skyrim-like lately - Kingdom Come Deliverence 2. When I was playing it, I kept being reminded of Skyrim, except that it kind of feels like what Skyrim was trying to be decades ago when the technology wasn't really there. It's got all the same systems - alchemy, forging weapons, sneaking, speech, combat - but they're all just vastly better, having been developed with the benefit of many years of experience, better technology, and a lot of money. When I was playing this game, with its incredible combat, its populous and intricate towns and cities, its great potion brewing mechanics, I couldn't help but wonder why on earth others were bothering with the Oblivion remaster?

And indeed it seems that most people briefly messed around in Cyrodiil and promptly moved on, because the game, while nostalgic for many, just isn't very good value compared to the amazing RPGs that can be made now. The only thing KCD2 is lacking is the ability to define your own character, which is undoubtedly still a huge draw for the Elder Scrolls and its imitators. I would die happy if Warhorse made a fantasy RPG where you could design your own character and I could play dress-up with my very own Blorbos in photo-mode.

Also, hardest of hard agrees on the superiority of Morrowind's magic system. Teleportation was so incredibly useful and satisfying, particularly in the main quest, as was levitation, chameleon, all of these fantastic spells and magic items make Morrowind so much more fun to play. Is it balanced? No, but in a way that's preferable - I found exploring in Morrowind so much more compelling and rewarding, because you would often find incredibly useful items that you'd still be using countless hours and levels later, which creates a strong incentive to keep exploring, whereas in Skyrim it's just predictable, incrementally better generic loot (which you couldn't even sell for a fair price without mods, because merchants were so inexplicably poor).

Great article.

In honor of the late Julian LeFay (RIP), features I really enjoy from Daggerfall that I think ought to make it into whatever game happens to be the next Scrolls-like.

1) Class-based familiarity and disposition. This is very fun for inhabiting a character, which is the part of systems-driven games that I don't think you cover very much here. The environment is important, but another very crucial component of these games is getting to feel not just like you are an actual adventurer dealing with various adventurer problems, but that you are a *specific* adventurer dealing with various adventurer problems. To recap for those unaware, in TES 2 Daggerfall, you can make a character who is more popular with the lower or upper classes of a city. Your cutthroat bandit type could have an easier time getting along with regular folk, and your majestic knight is highly appreciated by the nobility. This is much more interesting than just "i'm generically charismatic and everyone likes me OR i am generically dull and no one likes me"

2) Timers on quests. This is incredibly controversial and it probably won't be added, but I think it should at least be added to the survival/hard mode/whatever. The fact that almost all quests in daggerfall have a timer on how many (in-game) days you have to complete them requires you to prioritize your time. Part of what enables this system is the fact that a lot of the quests are repeatable and procedurally generated (which personally I really enjoyed, but I know that's not everyone's cup of tea), but the game is not afraid to make you fail even very important quests because you took too long.

3) Money and finding work matters a lot. Because you have a timer on your quests, you may often find yourself wanting to get places quicker. While DF (unlike Morrowind) has unlimited fast travel, the travel takes in-game time, and fast*er* travel requires stuff like riding a boat, or buying a horse, which costs money. Merchants also actually sell a lot of good stuff that is not easily outmatched by things you find in dungeons, unlike the later games. In turn, this means getting money by doing basic work for various factions matters a lot more, which synergizes well with the procedural contracts and faction reputation systems.